In this blog series, we look at 99 common data viz rules and why it’s usually OK to break them. Here are all the rules so far.

by Adam Frost

‘Always label your axes’, says the peerless Nathan Yau on his flowingdata blog. Otherwise your audience ‘doesn’t have a clue’ what they’re looking at. Add data labels to your bar whenever your audience ‘needs to know the individual values’, says Dave Paradi. Place these labels ‘inside or just outside’ the bar.

But there are many ways to explain to an audience what your chart contains. Chart labels aren’t always the best tools for the job.

In this post, I will look at the three types of labels: axis titles, axis labels and data labels. I will look at them in the two main types of bar charts: vertical and horizontal. I will argue that deleting as many labels as possible is the only way to make a bar chart an effective communication tool.

Vertical bars

The first thing to say about vertical bars is how unfailingly they mangle text. Like the scorpion in the parable of the scorpion and the frog, it’s in their nature. Of course they will promise to ferry your story to the other side of the river without rotating or hyphenating or abbreviating your labels, or making everything overlap. But as soon as you trust them with your data, they will sting you again, and drown you both.

Yes, I know vertical bars are the most accurate chart, they deliver pattern perception and table look-up, Cleveland and McGill, yada yada yada. But all of this only applies to the bars. I agree that those shapes are superb at representing distinct, legible values. But the bars are only half the story, and the half that nobody will ever get to if they can’t decipher what any of it means.

Let’s document all the ways that vertical bars mutilate text and see if we can’t pry the story from its cold, dead hands. The y-axis first.

i) y-axis title

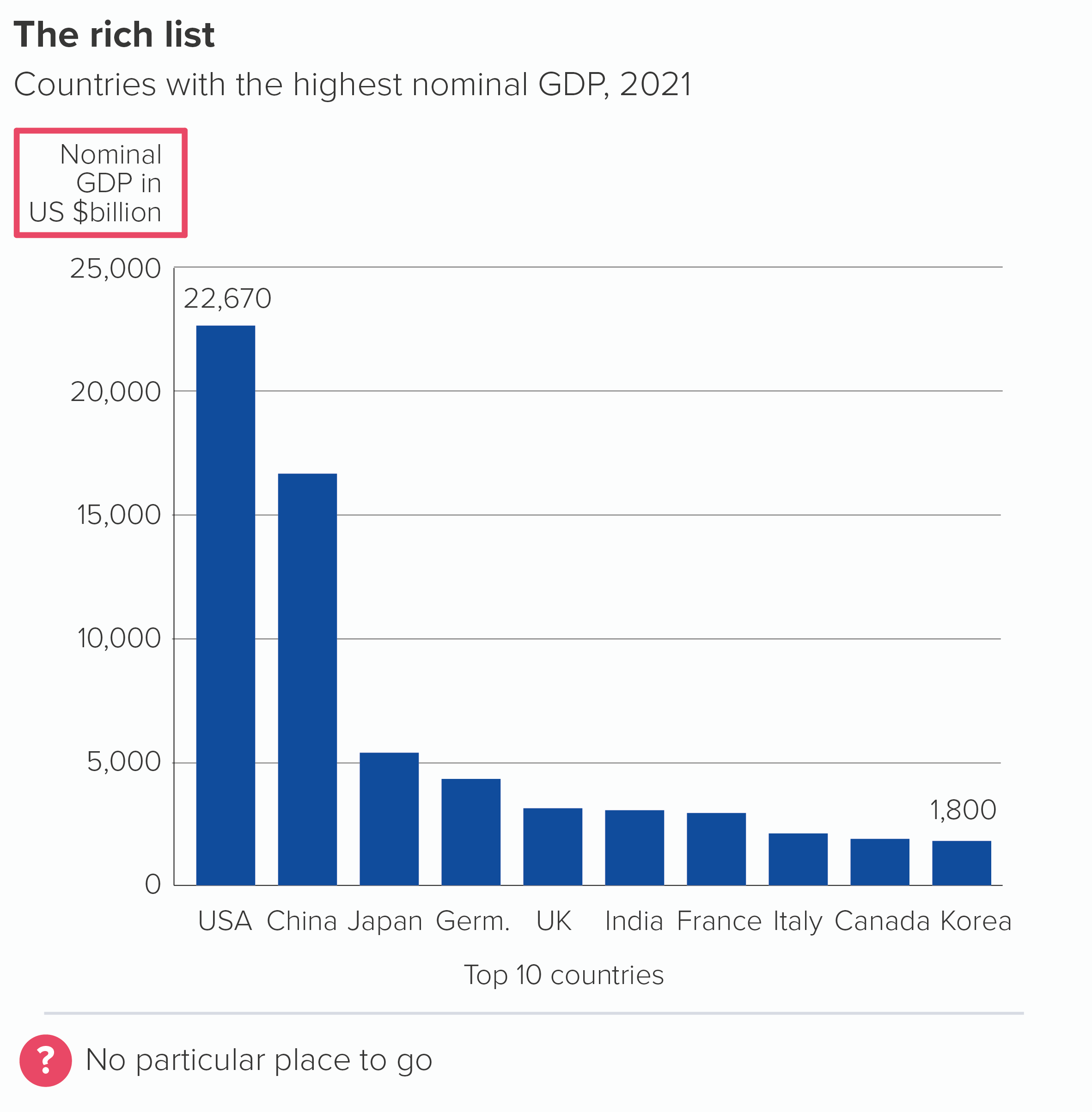

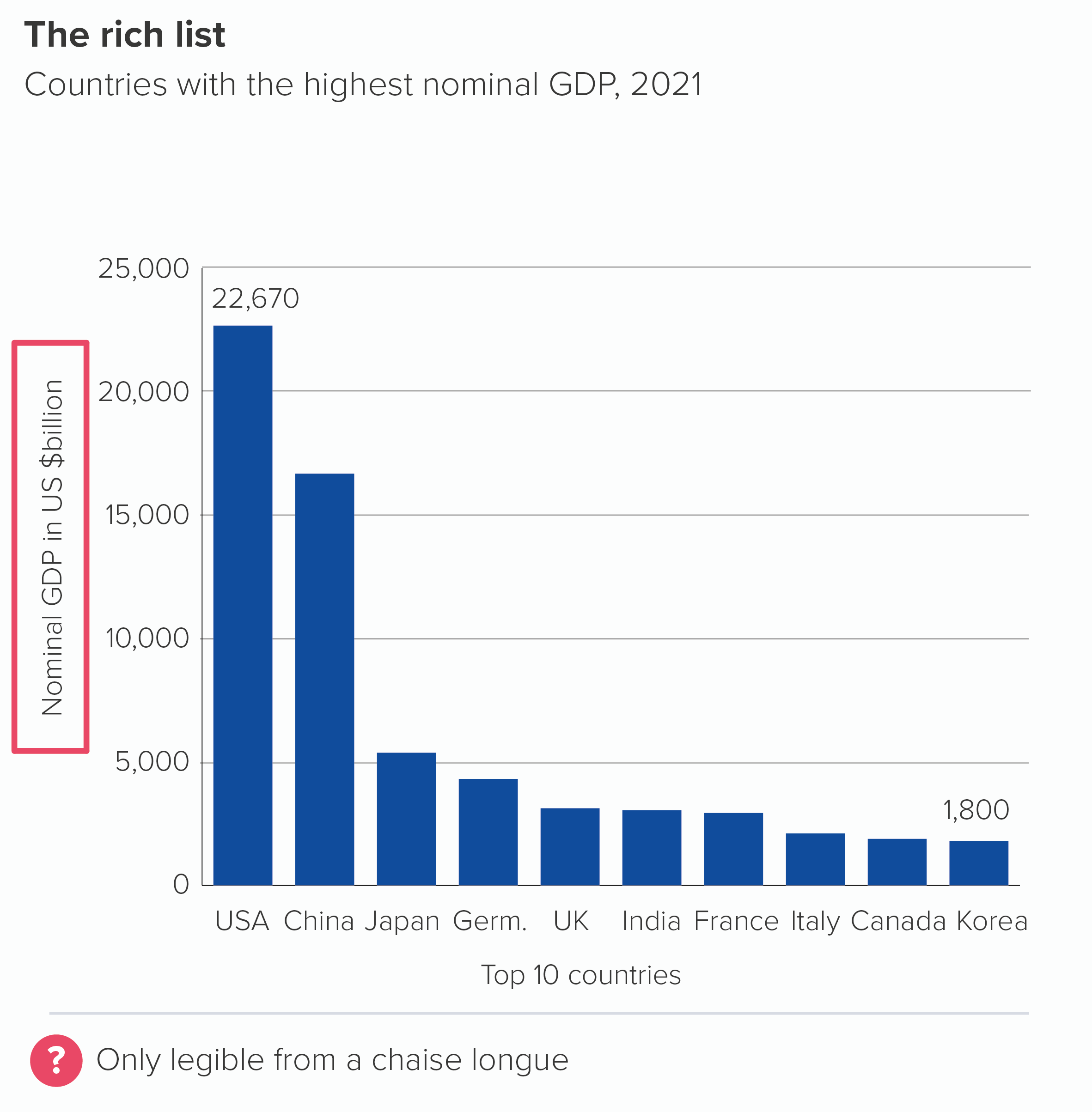

The y-axis title tends to get put in one of two places, floating at the top of the axis or, more frequently, rotated and squashed vertically beside the axis values. Neither option is intuitive or easy to read.

The easiest way of solving this - and this will be our solution for many of the issues below - is to remove it, and bump the key information up into the chart subtitle, where it will be horizontal, legible and hard to miss.

In the example above, the chart subtitle would become: ‘Countries with the highest nominal GDP, 2021 (in US $billion, 2021)’.

ii) y-axis labels

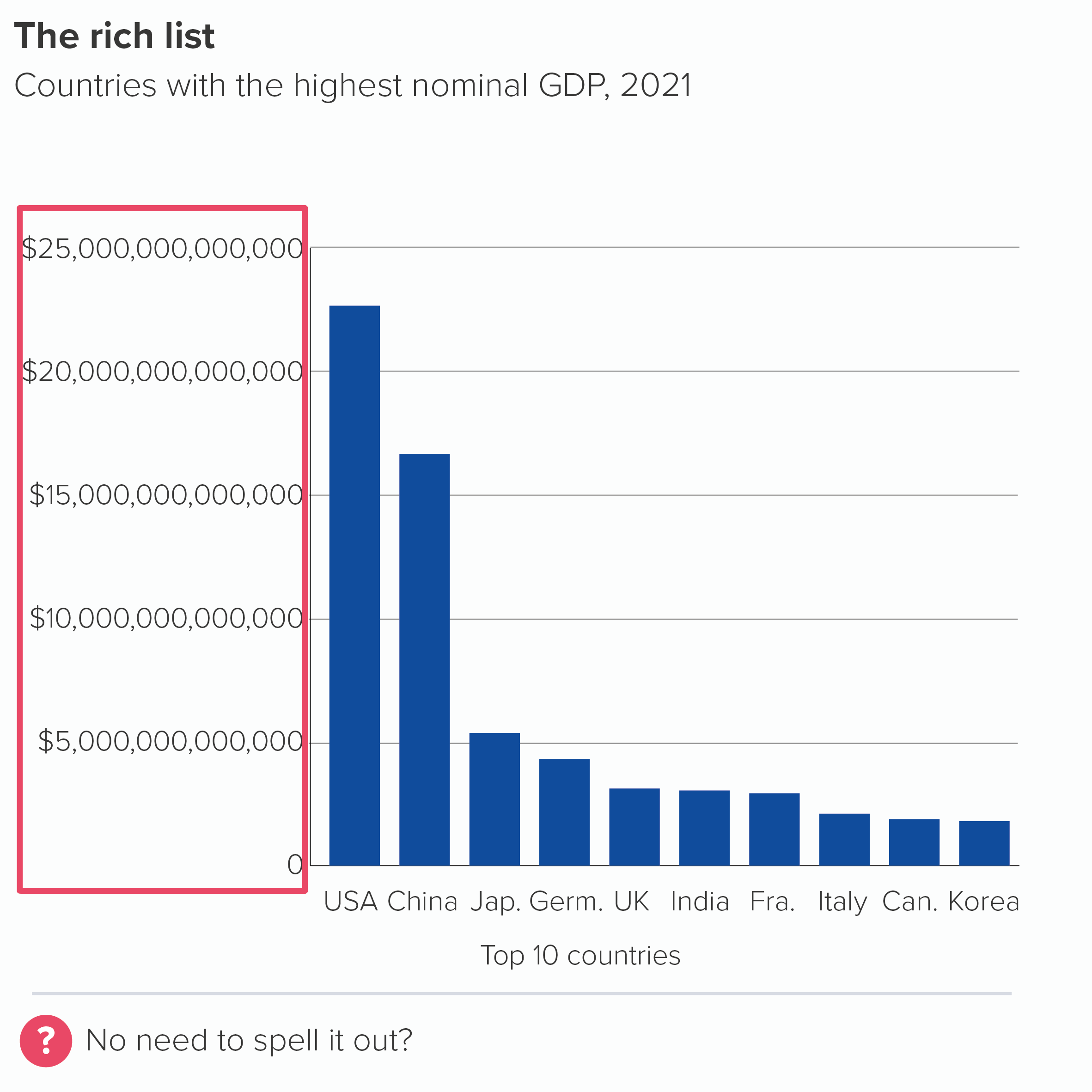

The labels for your y-axis numbers will fit just fine unless you are inconsiderate enough to require large numbers to be visualised (values of 1,000 or more) in which case these labels will need more horizontal space and push everything right, leaving less space for the actual chart.

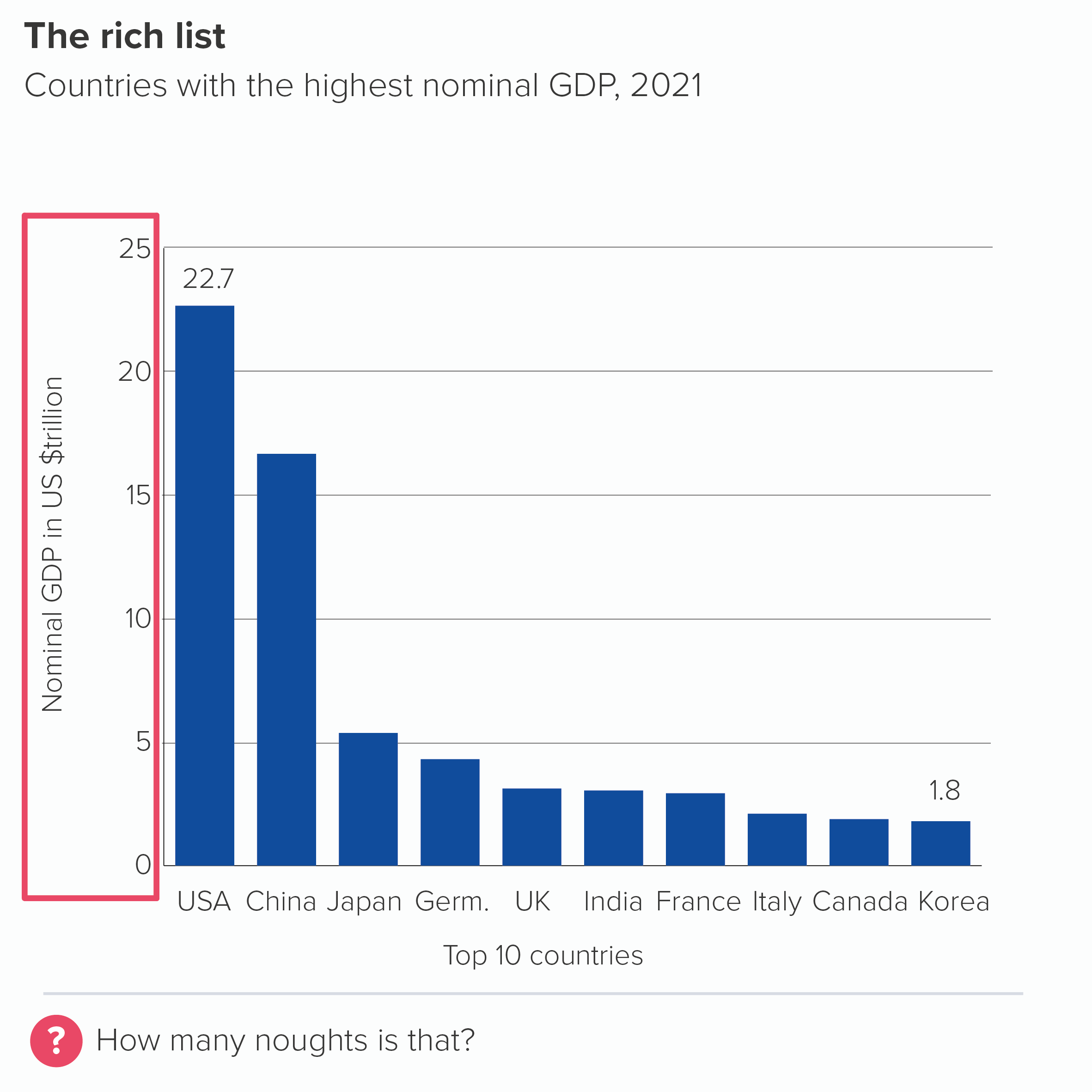

Alternatively, you can keep your axis labels short but this will often requires some kind of abbreviation in your chart subtitle, for example, ‘amount in ’000s’ or ‘distance in millions of kilometres’, which can confuse your audience, as they first look at the axis, realise that those numbers look implausible (US GDP is $22.7?), look up at your axis title or chart title, work out what you have done, and then heave a deep sigh as they realise they will mentally have to add ‘000’ or ‘000,000,000’ or whatever it is to all the numbers on your axis.

How many zeroes is a trillion again? Plenty of people have no idea. Is it 12? And is a billion 9? Or hang on, there’s a US and UK billion, isn’t there? And what about when we need to start measuring GDP in quadrillions? How many zeroes is that?

Of course, many charts share this problem (e.g. lines, scatters), but because vertical bars also have other problems on the x-axis (see below) and because there is no space to fit long labels on those narrow bars (also see below), it is more important to solve y-axis problems with vertical bars, or the readability issues can cascade down through the rest of the chart.

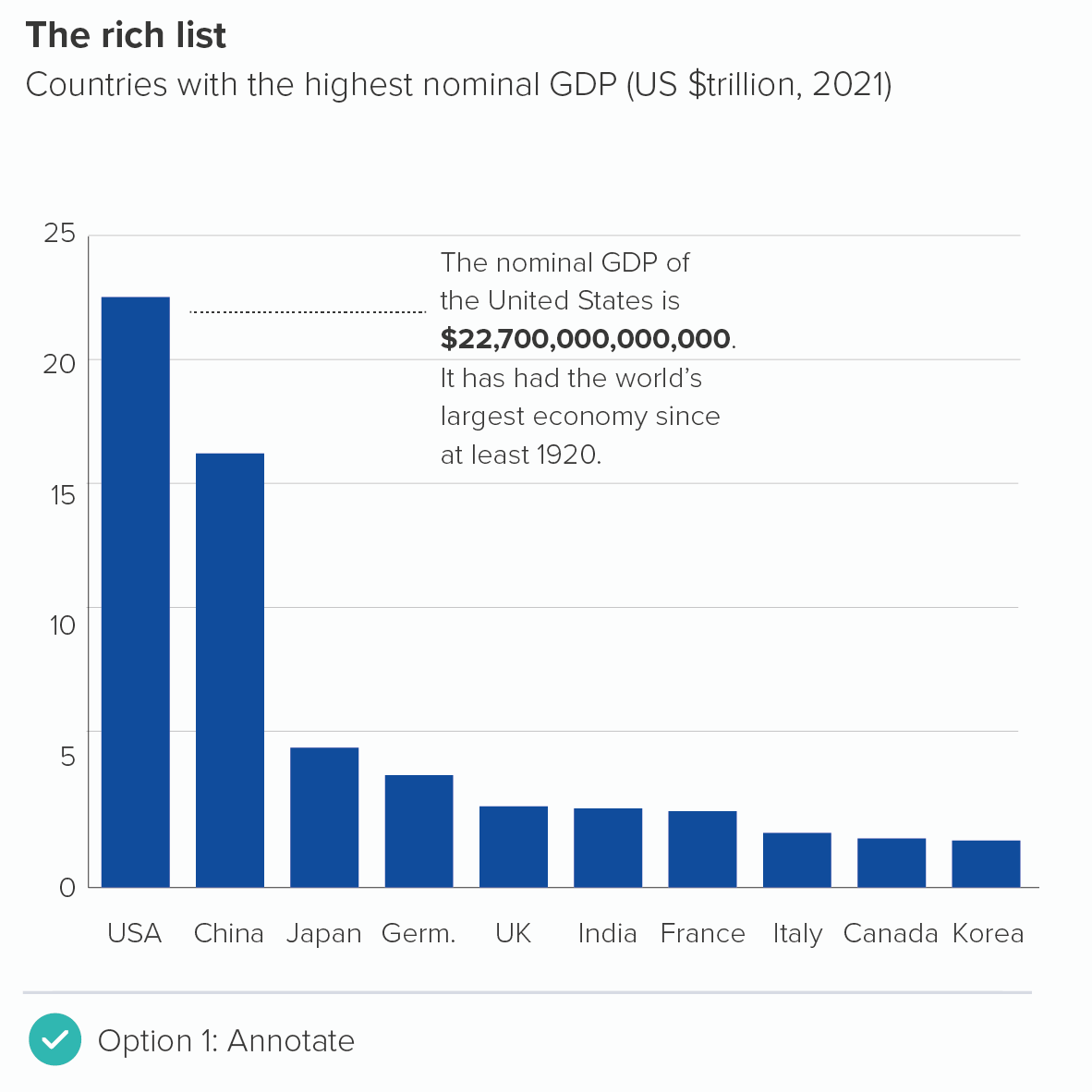

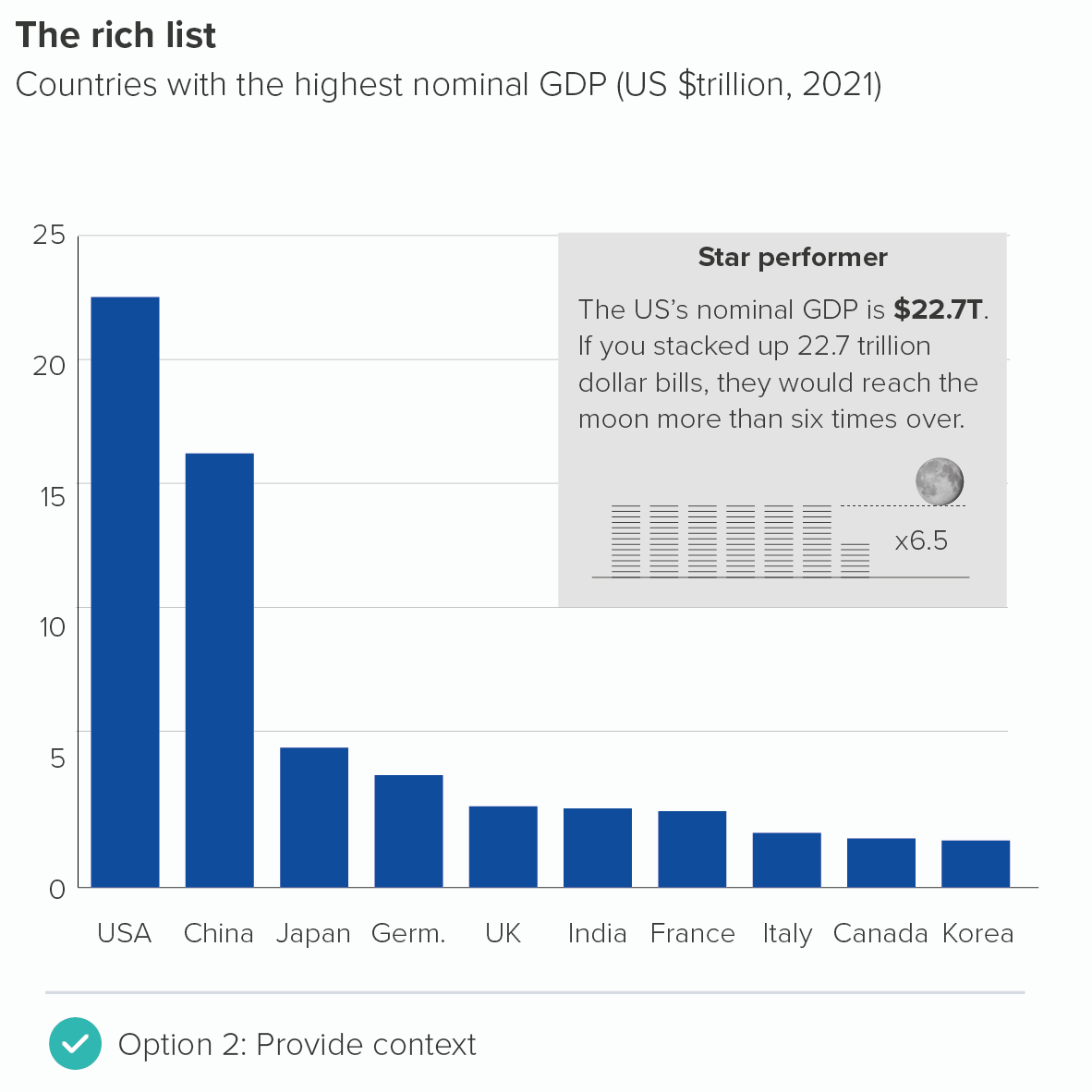

One way of addressing this problem is to keep the y-axis labels short, but to use an annotation to spell out any potentially confusing numbers (the first chart below). Or you can use a call-out box to contextualise one of the key numbers (the second chart below) so even if your audience doesn’t know the number of noughts in a trillion, it doesn’t matter, because at least they have a meaningful comparator.

(The 6.5 times to the moon stat is true, by the way - assuming a dollar bill is 0.11mm thick).

Naturally, if you are presenting to accountants or bankers or people who know exactly what the abbreviated numbers mean, this won’t be necessary. But other audiences can easily misunderstand the differences between millions, billions and trillions, and it’s a good idea to help them out.

iii) x-axis title

I won’t spend too long discussing x-axis titles on vertical bars because in almost all cases, you should just delete them. If you have the x-axis labels ‘2001’, ‘2002’, ‘2003’, ‘2004’ and you feel the need to put ‘Year’ underneath, or if you have the x-axis labels ‘USA’, ‘China’, ‘Japan’, ‘Germany’ and you feel the need to put ‘Countries’ underneath, then ask yourself: who is that helping - You? Your audience? Why?

The only possible justification for using an x-axis title is that you feel the x-axis labels are unclear. For example, maybe you’re using two-letter country codes: IE, IT, DE, FR and the like. You want to add the title ‘Countries’ so it’s clear what those cryptic glyphs mean. But if your audience isn’t familiar with two-letter country codes, why are you using them? And if your audience knows what these codes mean, why repeat that they are ‘Countries’?

As we saw with the y-axis, it should be plain from the chart title and the axis labels what your bars are representing. Run a Google Image search for bar charts in the Economist, the Financial Times, the New York Times or any other quality news provider of choice, and you will look for an x-axis title in vain. Good communicators strip out redundant information instinctively, and so should you.

iv) x-axis labels

Here we go. Those of a sensitive disposition should look away now. All of the horrors discussed above pale into insignificance compared to the havoc that is wrought by vertical bar charts on the average x-axis label.

This wouldn’t be such a problem if these labels weren’t the most important part of your chart (after your title). But they are. It’s where readers find the ‘Who’ in your ‘Who What Where When Why’ structure. It’s where the story bites.

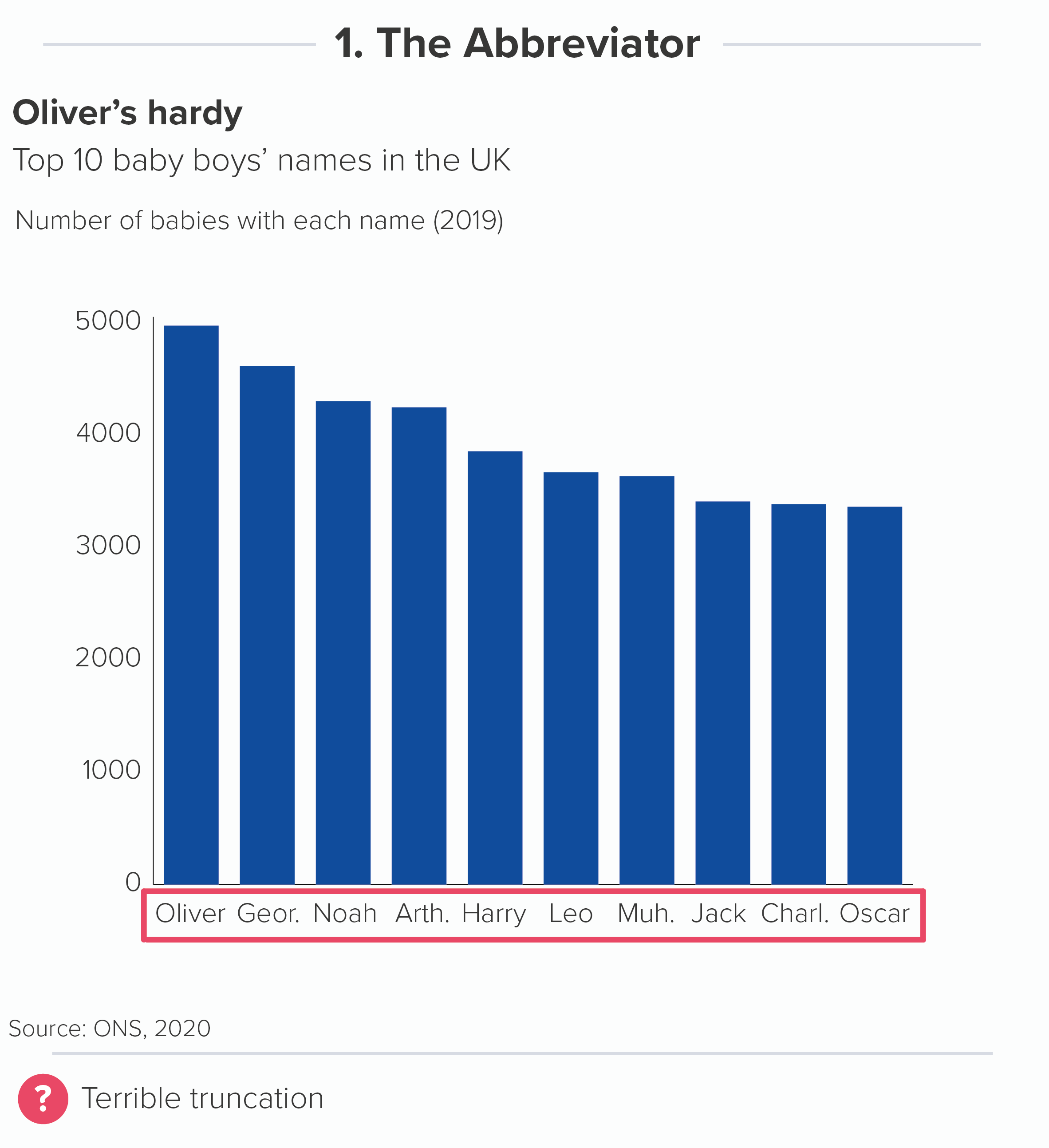

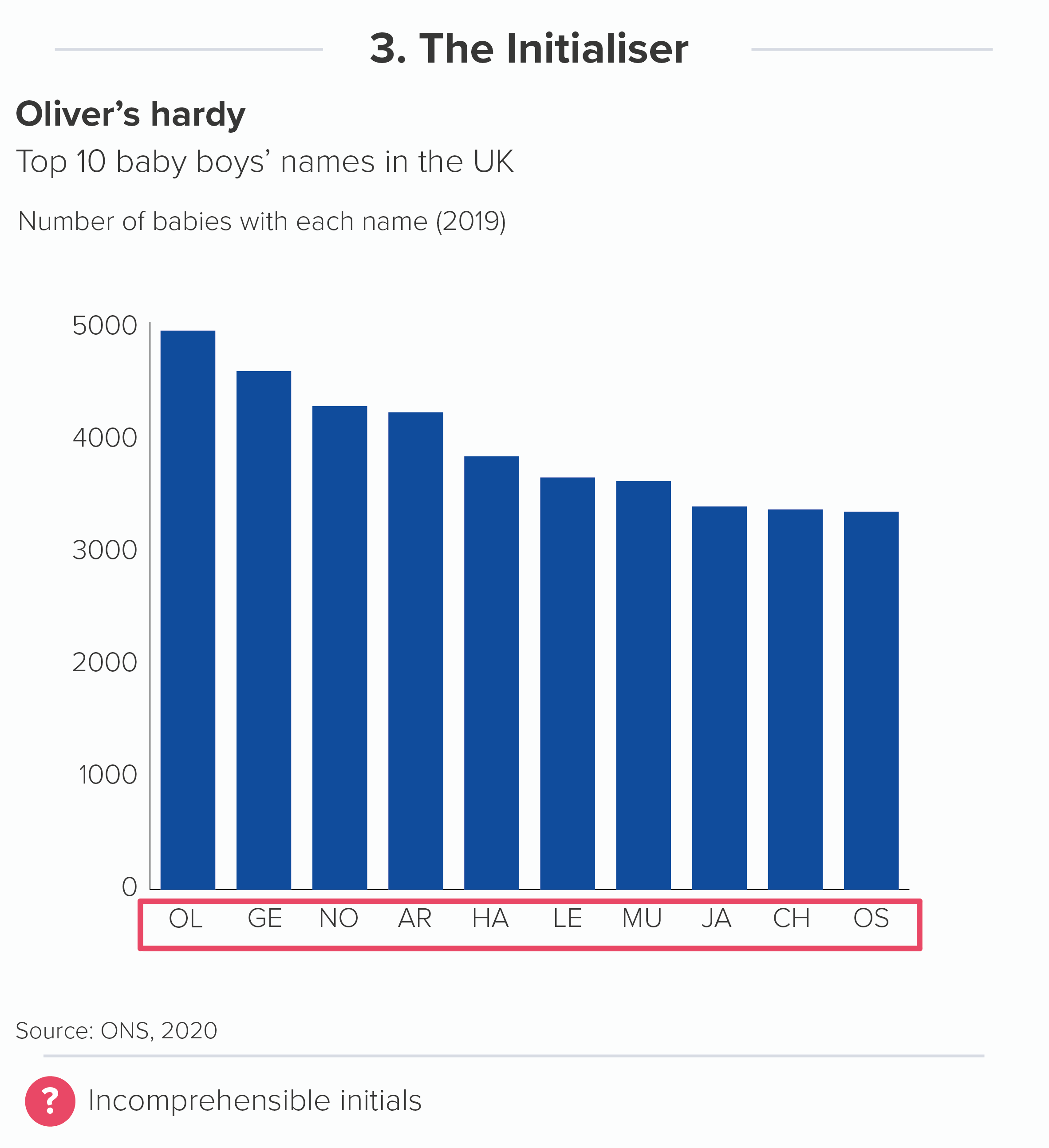

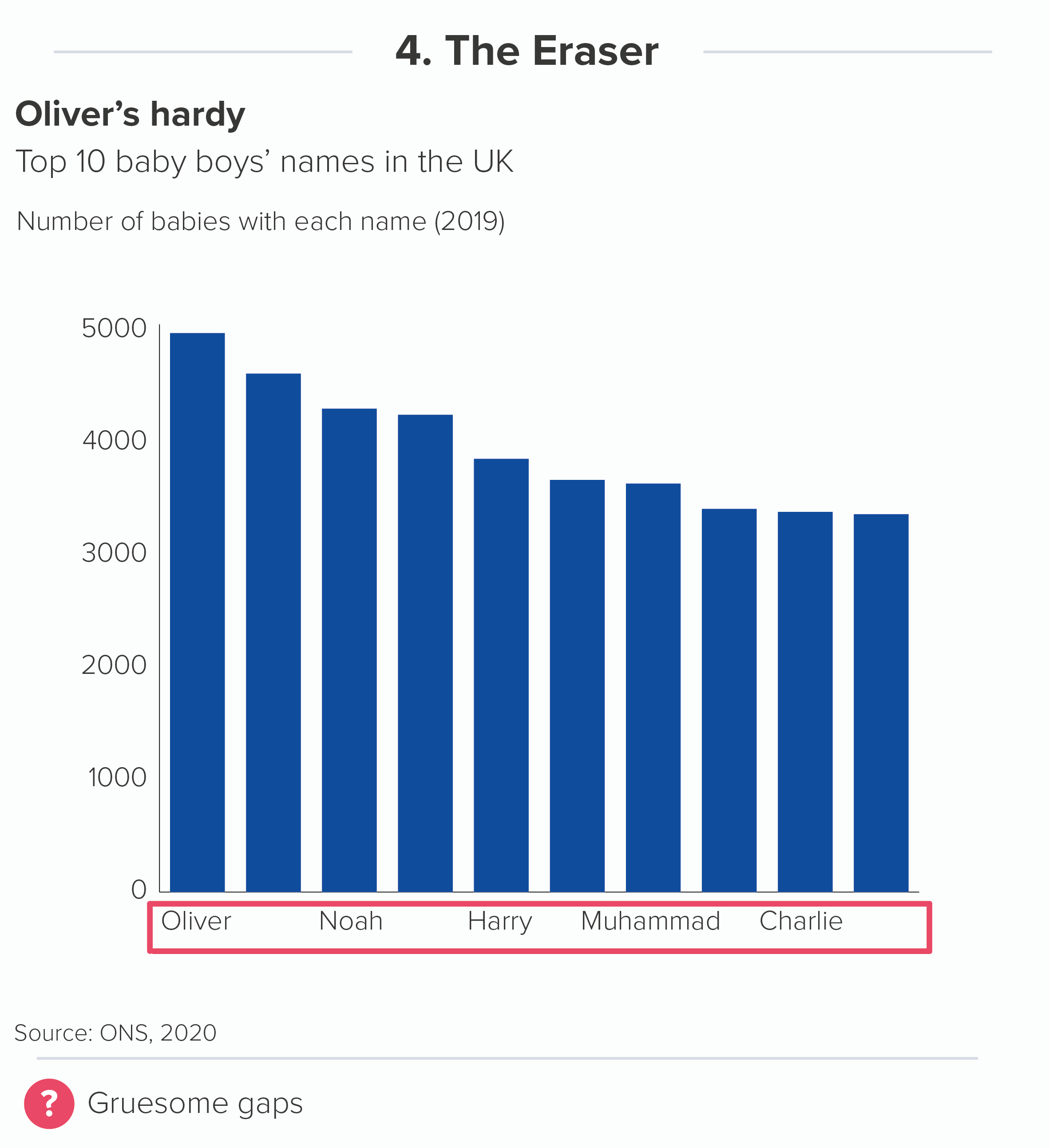

There are many creatively sadistic ways in which vertical bars persecute x-axis labels. To differentiate them, I’ve named them after (fictional) medieval torture equipment. Tremble as you look upon the blood-curdling spectacle of The Abbreviator, The Hyphenator, The Initialiser, The Eraser, The Minimiser, The Overlapper, The Spine Cracker and (worst of all) The Rotator!

Sometimes you will be extremely lucky and won’t need to employ any of these methods. All of your x-axis labels will be incredibly short. Or you will have lots of horizontal space and be able to fit more than a few labels in. But in the majority of cases, you will have to use one or more of these forms of textual torture. So are they ever justified, and what do you do when nothing works?

The Truncator: Abbreviation is fine when you have abbreviations that everyone understands (like dates - Mon for Monday or Jan for January) or where the context makes it clear when longer labels have been abbreviated (e.g. China, Japan, Viet., Myan.)

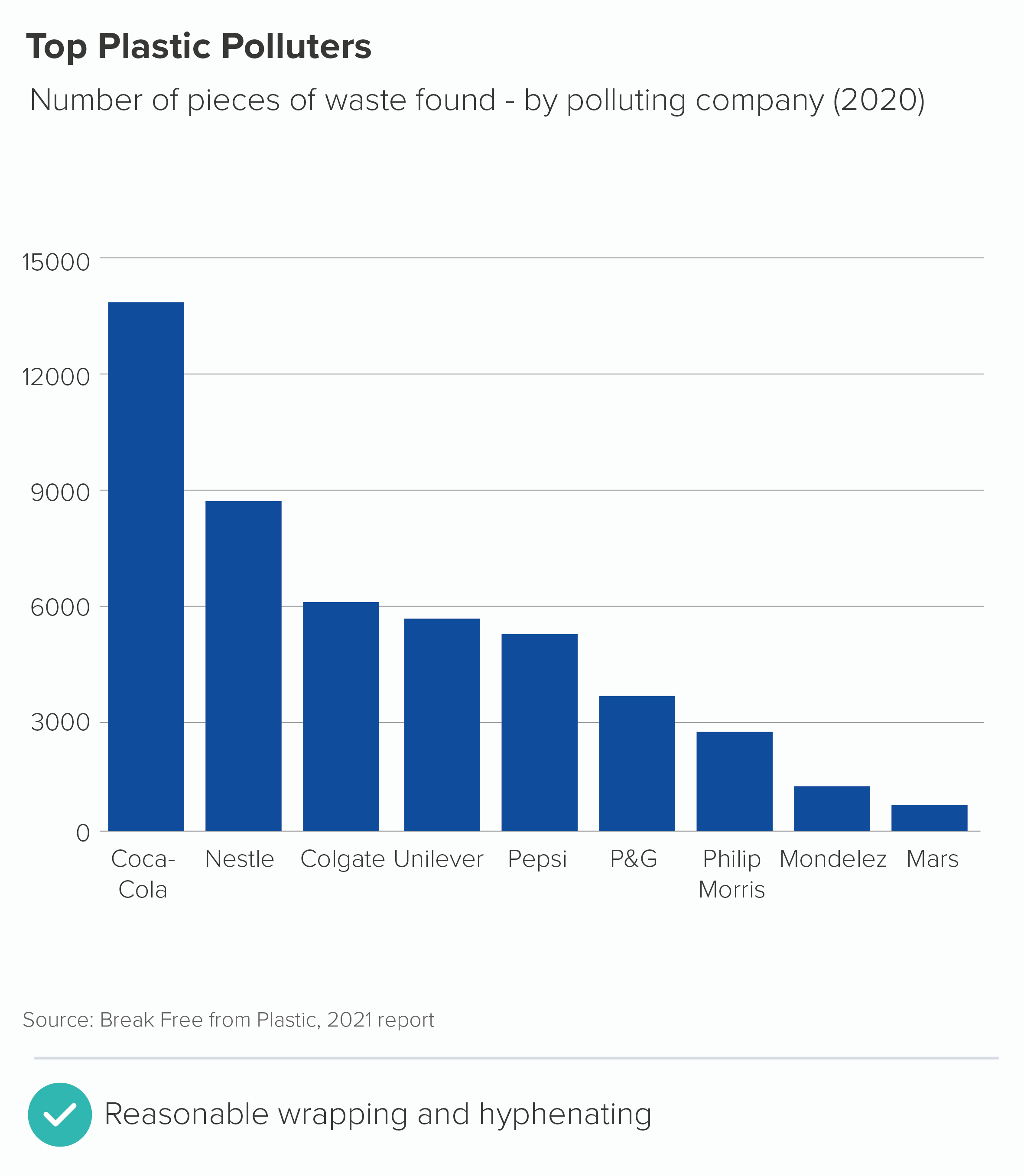

The Hyphenator: Hyphenating or text wrapping if OK is this is where a word or phrase would naturally break. E.g. June / 2016, or Coca- / Cola.

The Initialiser: This is legitimate if you are confident that your audience will understand the initials or acronyms you are using (e.g. SE for South East, EU for European Union).

The Eraser is fine for time series or other charts where the missing labels can be intuited from the labels that remain. Or when you have so many bars that labelling them all is impractical (see rule 17).

The Spine Cracker. This is fine when you have lots of bars and only want to label a few of them. But you don’t have to put all the labels on the x-axis; you can label the bars directly too (see below).

A combination: sometimes you might be able to combine a few of these - for example N. Ireland and East Mids would be understood by most UK audiences as Northern Ireland and East Midlands if it was a chart about regional performance. A chart for fans of phase 3 Marvel movies could happily use labels such as ‘SM: Far / from Home’ and ‘Capt. / Marvel’. These examples combine initialising, abbreviation and text wrapping.

Minimised, overlapping or rotated text is never justified under any circumstances. It makes the text harder to read than it would be in a data table, making a mockery of the whole visualisation exercise.

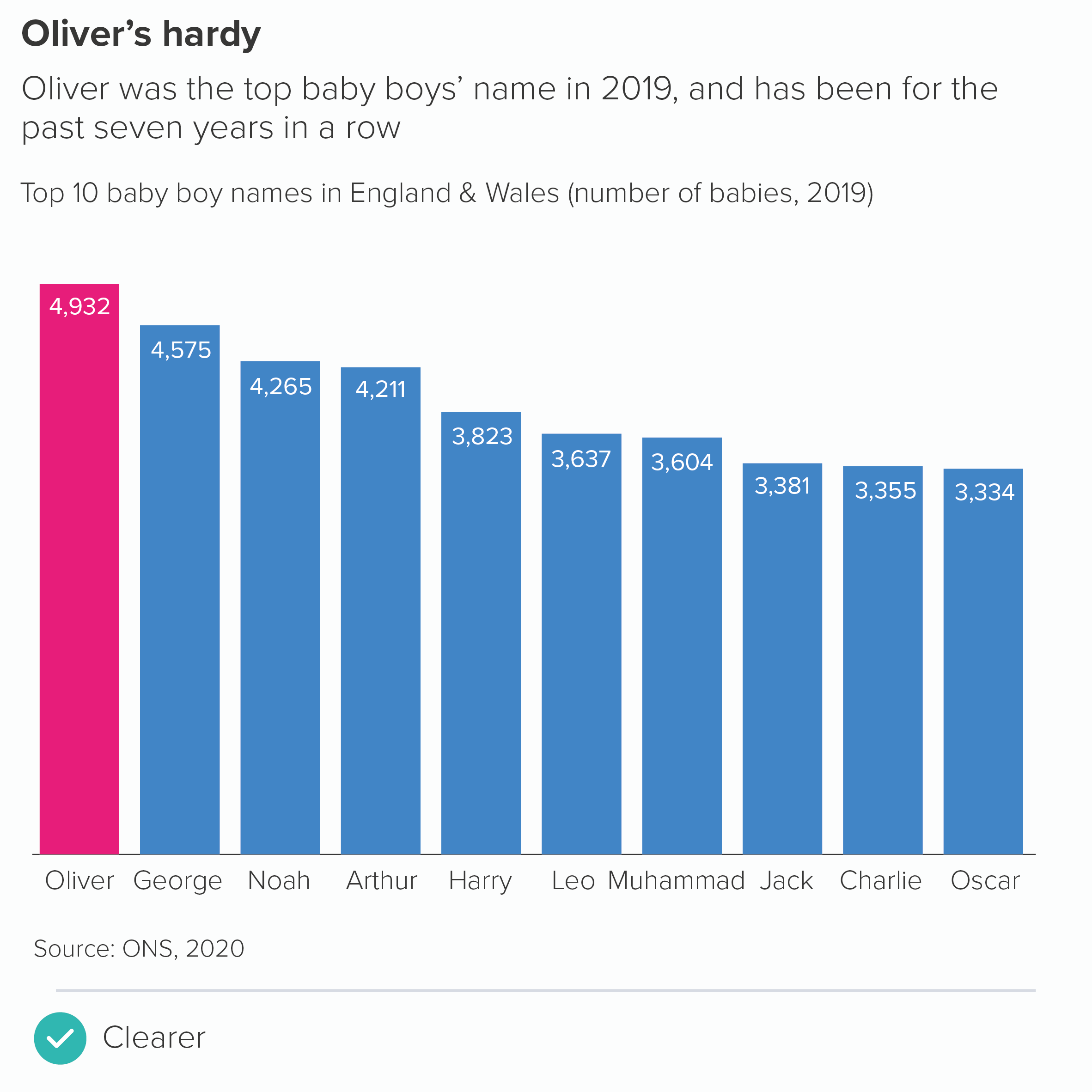

Sometimes you will try all the methods above, and they will all result in tortured text. The labels are long (or even just a normal length) and can’t be condensed. In these cases, you can switch to a horizontal bar, which we will look at more closely in a second. For now, I’ll just say that this can be a legitimate alternative in one or two specific instances. For example, the Top 10 boys names chart visualised earlier in this blogpost would be better as a horizontal bar.

However, in most cases, rotating the chart raises other narrative issues. More often, it’s best to consider an entirely different chart type (we suggested some in rule 16). We will look into these alternative chart types in later rules.

v) x-axis data labels

To finish with vertical bars, another text issue concerns the data labels - the numbers at the top or inside the top of the bars. Because vertical bars are narrow shapes, these data labels can be too wide to fit inside the bars, and if you put the labels outside, they may overlap with neighbouring labels when the bars are of similar heights, increasing textual clutter. Alternatively, you can leave data labels off, which means you have to cover your chart with gridlines so the values can be estimated, which isn’t ideal either - from a visual or cognitive point of view.

As with the x-axis labels, turning a vertical bar into a horizontal one can occassionally be a good solution for this, which we will look at shortly. However, if vertical bars are the right fit for the story, the ideal way to treat data labels is as follows:

first, ensure you don’t have too many bars (see rule 17) so your labels have a fighting chance of actually fitting in

contract the numbers as much as you can, e.g. 1,800,000 becomes 1.8 and then you place ‘value in millions’ in the chart title. However, be aware of the common usage guidelines mentioned above, and use common sense to work out whether spelling out the number is required.

you can reduce the font size for your labels slightly. Although ideally you shouldn’t use too many different font sizes on a graphic, the exact data values are of secondary importance to most readers, so it’s fine to signal this in the information hierarchy by (consistently) using a smaller size for the datapoints

wherever possible, label the bars directly - don’t rely on gridlines. This means you can…

remove the y-axis. If the bars have data labels, you don’t need it. This also gives you more horizontal space, which makes it more likely that all your data labels will fit. You can also...

remove the gridlines. Again, if the numbers are on the bars, what’s their purpose? (We’ll look at this in more detail in a later rule). All of this deleting gives you a much clearer, cleaner chart.

wherever possible, put your data labels inside the ends of the bars. This frees up more vertical space, which means your bar chart can be taller, accentuating the drama, and making the differences between the bars more noticeable. Only very short bars should have labels outside.

As a side benefit, all of this data label tinkering should mean you have more space for your x-axis labels too, meaning that the hacks in section iv) above might just work.

vi) Mobile first?

There is one final problem. Just as video killed the radio star, so mobile phones killed the vertical bar. Even if you manage to have a vertical bar that overcomes all the legibility issues mentioned above - not too many bars, short x-axis labels, no need for a y-axis, data labels all fitting - even if you manage to get it looking clear and clean on your 16:9 Powerpoint presentation or laptop screen, someone will open it on their phones and be able to read none of it. Or they might magnanimously agree to rotate their phone, I suppose. (I did see it happen in user testing once). So if it is imperative that your chart is legible on a mobile phone, then consider a different chart type. And one of the chart types that is sometimes considered - a horizontal bar - will be discussed next.

Horizontal bars

Horizontal bars are much more readable on mobile portrait, they can be easily scanned and scrolled through.

In fact, horizontal bars are perhaps the easiest chart to read full stop, overcoming almost all of the legibility challenges listed above. Text labels can be long or wrapped, and it rarely matters; data labels can be long or complex and it rarely matters. They will usually fit and they will be horizontal.

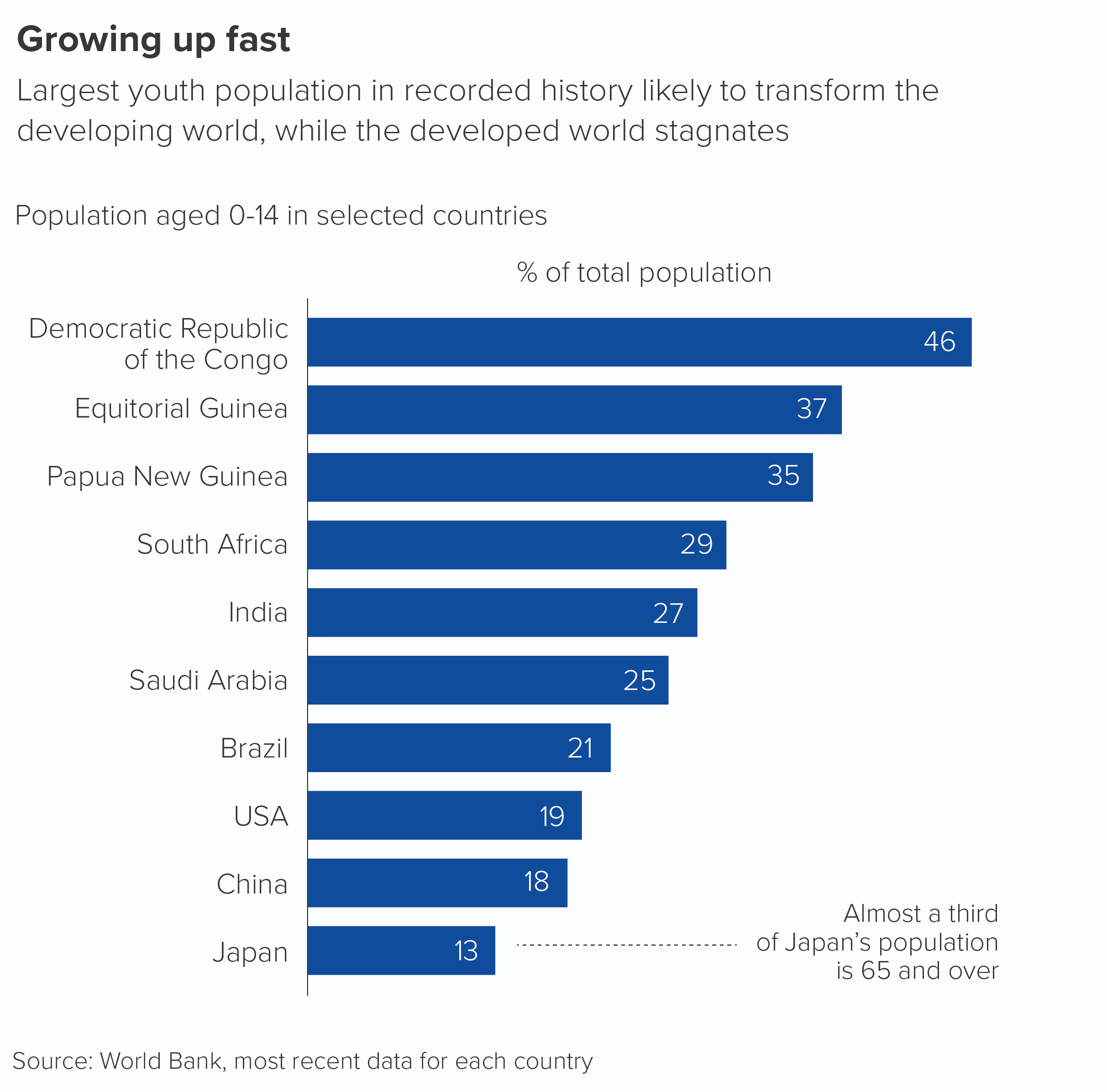

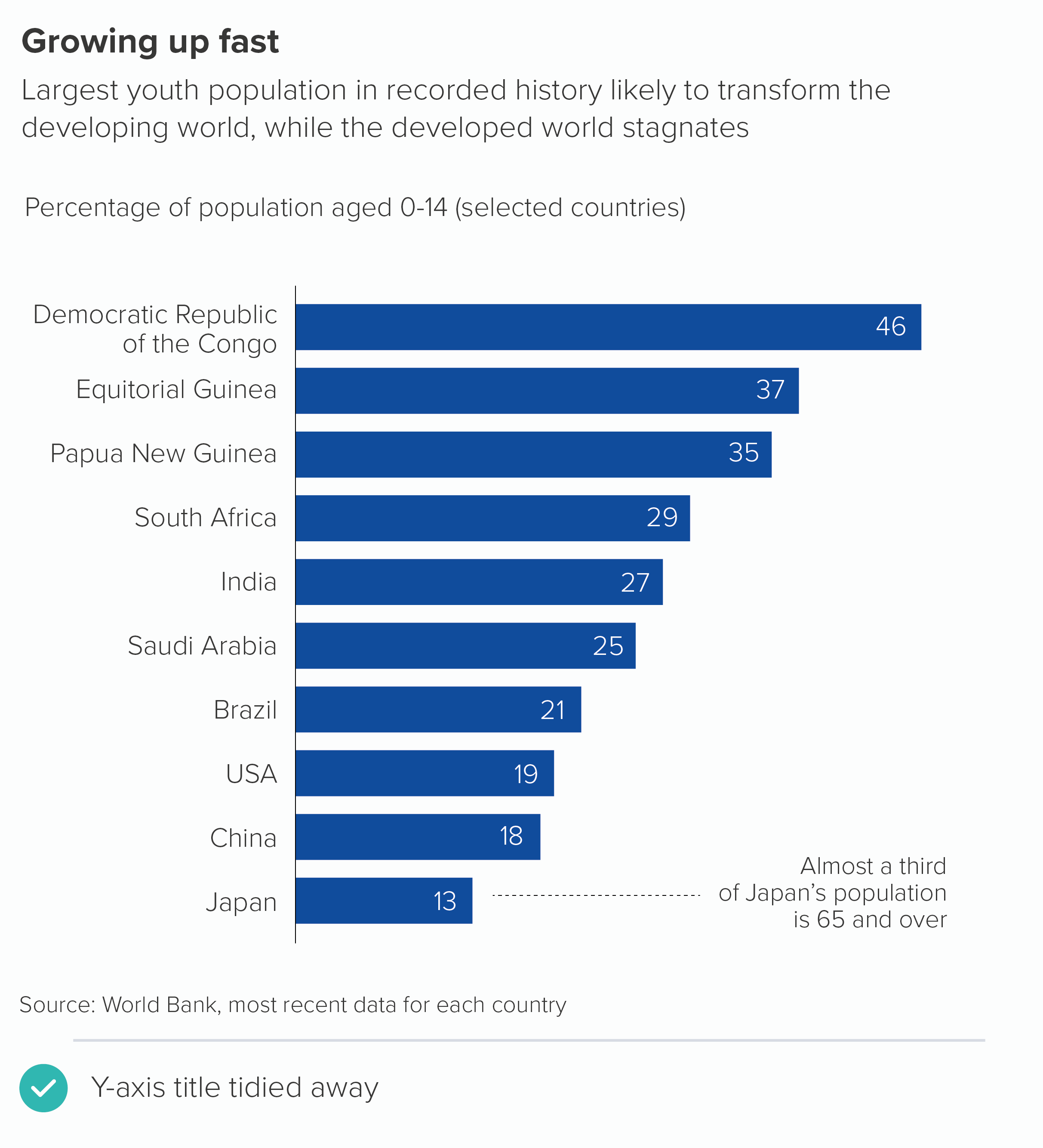

Compare the reading experience of these two charts. The vertical bar first. Let’s imagine you wanted to find out the name and value of the third-placed bar (Papua New Guinea) and then compare that to the final bar (Japan). This might be your journey through the information.

On a horizontal bar, it is something like this.

Let’s think about the spatial journey too. A vertical bar needs to be composed a bit like a narrative painting, with the designer clearly flagging up the desired read order, defining what art critics call areas of focus so the reader clearly understands that this isn’t going to be read in the usual way, like text, but is a bespoke structure that suits the rhythms of the story: start at the top, then take in the shapes in the chart, maybe look at the y-axis label, move to the bottom, find the country you’re interested in, then maybe glance back at the subtitle, then look at the bar label, up and across to any annotations. Your eye has to rove around the canvas to follow the narrative thread.

A horizontal bar poses none of these compositional challenges. Provided that the designer has ranked the bars from largest to smallest (which is always preferable, as we saw in rule 19), then you read them as you would read a page of text, in a z-order, left-to-right, your eye scanning along and down, along and down. It is much harder to get lost.

So why don’t we use horizontal bars all the time? It makes our rule - always label your bars and axes - so much easier to follow. We seldom need any textual hacks, as we do with vertical bars, there is less call to abbreviate or hyphenate or omit. Just pour in the data and the text usually looks after itself.

However, the ease with which we can label a horizontal bar chart is also indicative of its key weakness. If a vertical bar foregrounds those dramatic shapes, barging the text into the margins, then horizontal bars do the opposite, foregrounding the readability of the text and relegating the shapes to a supporting role.

A rectangle stretching across a page rarely causes the pulse to quicken, it is more like the agonisingly slow progress bar when you are installing new software, or the bar on your phone showing battery life: a factual declaration of current status.

At their best, horizontal bars can evoke the idea of a race, horses galloping towards a finish line, one of them ahead by a nose. For this reason, they are often used to show growth towards a target, or versus an average.

But for most stories, horizontal bars - flat on their backs - simply do not have the same visual impact as those gravity-defying vertical bars, stretching towards the sky.

More importantly, vertical bars embody how we picture difference in our minds: as bigger, smaller, rising, falling. We don’t think of growth as wider, further to the right, inching along a flat surface. Higher up is also understood as more important, more interesting, more visible. Moving something left or right does not imply that it is more or less worthy of our attention. (In fact, if things are going sideways, it means something else entirely).

For me, vertical bars also signal more clearly that these shapes are grouped, a family, all representing the same thing. Perhaps because they suggest buildings side by side, or wooden poles in a fence, or even people standing shoulder to shoulder. The shapes share the same patch of ground. Horizontal bars, arranged one above the other, are clearly separate, like different country flags on the same pole. (Or a row of beds in a dorm, each containing a separate sleeper).

There is also the accuracy issue. In rule 16, we mentioned that bars are the most accurate chart. However, if accuracy is your religion, then technically the vertical bar should be your holy of holies. As Tamara Munzner explains in her excellent study, Visualization Analysis and Design, it is easier for us to compare the tops of vertical shapes, than the ends of horizontal ones. (AK Peters, 2014, p118).

I’m digressing here. But what I’m trying to emphasise is: it’s easy to think when you have a vertical bar with unreadable labels that you can simply rotate it - et voilà! - you get the same chart with more readable labels. But a horizontal bar is an entirely different chart: as different from a vertical bar as a line chart or a pie chart would be. You have made the text readable, but at a potentially fatal narrative cost.

Because of the meanings baked into the shapes, vertical bars excel at telling specific stories - comparison, change over time, distribution, waterfalls.

Horizontal bars excel at others - ranking, distribution, funnels, timelines. (See rule 16 for more on this).

Which story are you trying to tell? By rotating your vertical bar by 90 degrees, you might have got readable labels, but will anyone understand them if the shapes and the story don’t match?

The truth is, the solution to a vertical bar with unreadable text is only occasionally a horizontal bar. Perhaps if you have a ranking story - but otherwise, unlikely.

Instead, try the hacks outlined in the first part of this article and if these don’t work, drop the vertical bar and choose a chart type that actually suits your story.

Finally, I’ve been extolling the text-friendly properties of horizontal bars, but it’s worth mentioning the rare occasions when the rule ‘Always label your bars and axes’ doesn’t work for this chart type, and how we might address these issues.

i) y-axis title

As with vertical bars, there is no real reason to ever include a y-axis title on a horizontal bar. Certainly if you feel, for the sake of clarity, you have to include it, never rotate it and wedge it behind the axis labels. Put the axis title above the labels. Even better, remove it and make it clear using the title or subtitle what those labels represent

ii) y-axis labels and data labels

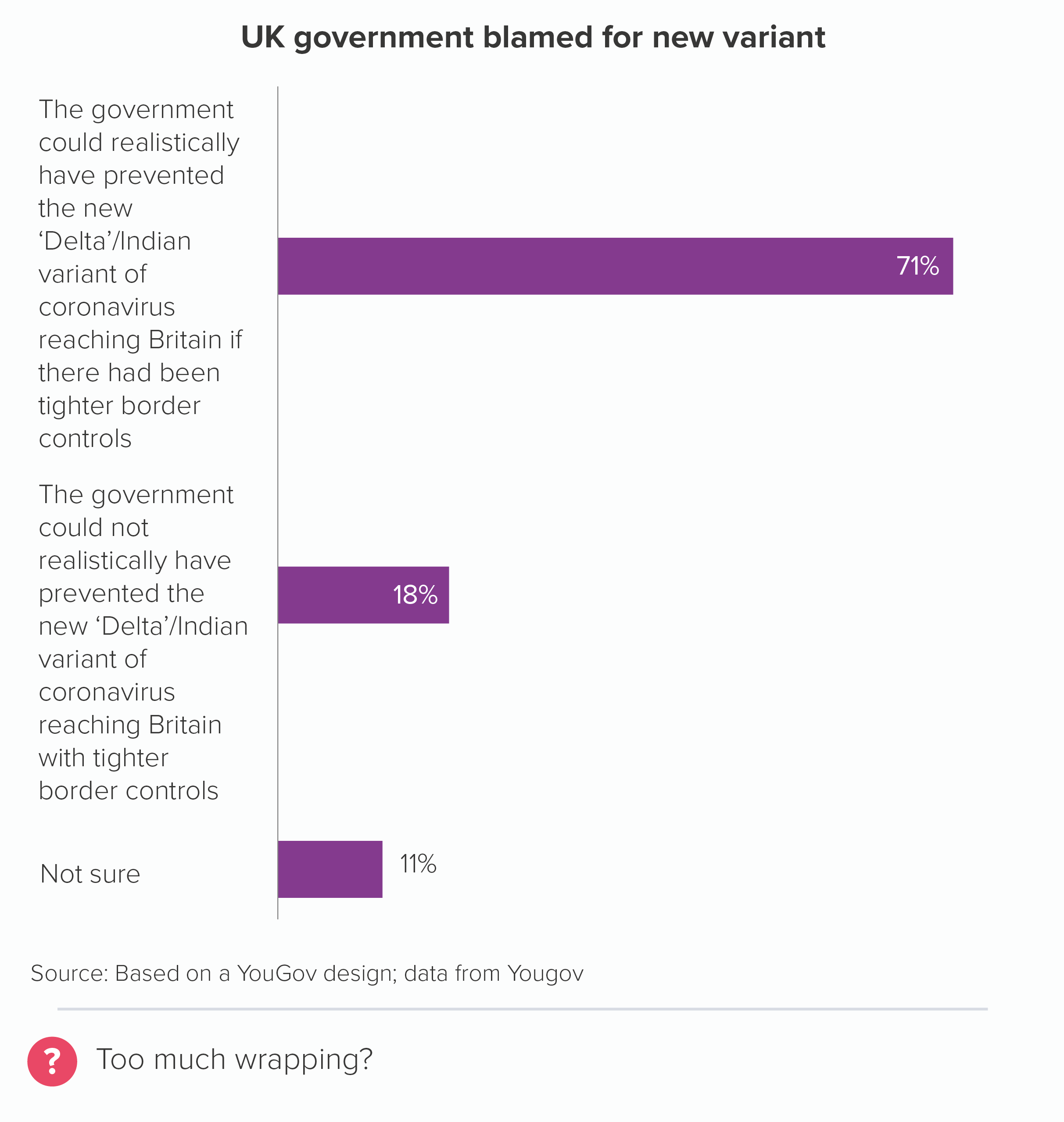

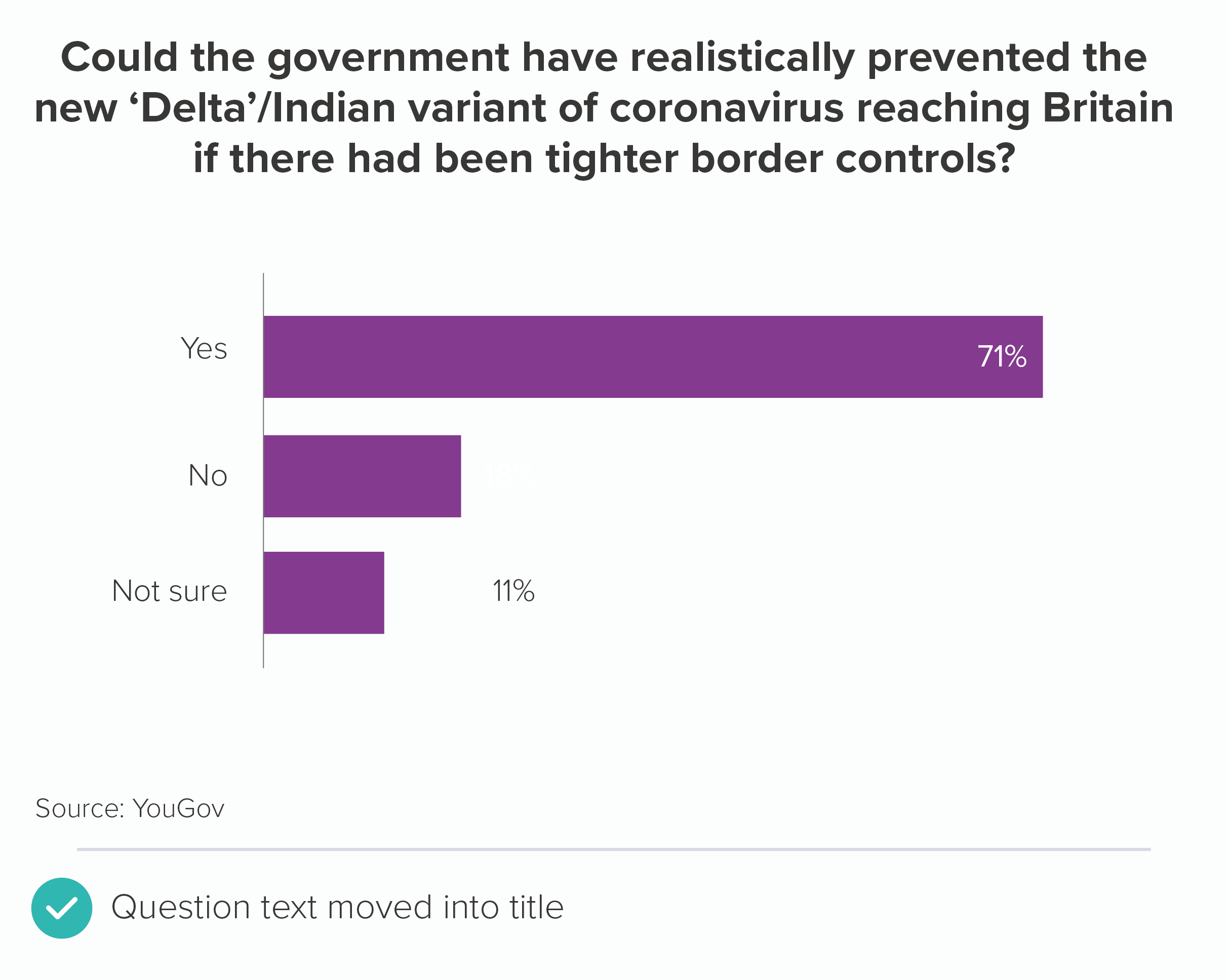

Just as the amount of horizontal space available to you can mangle the x-axis labels on your vertical bar, so it can do the same with horizontal bars if the labels are too long. This is particularly the case where the labels represent statements or opinions. You will need to wrap or abbreviate the sentences or there will be no space for the actual shapes.

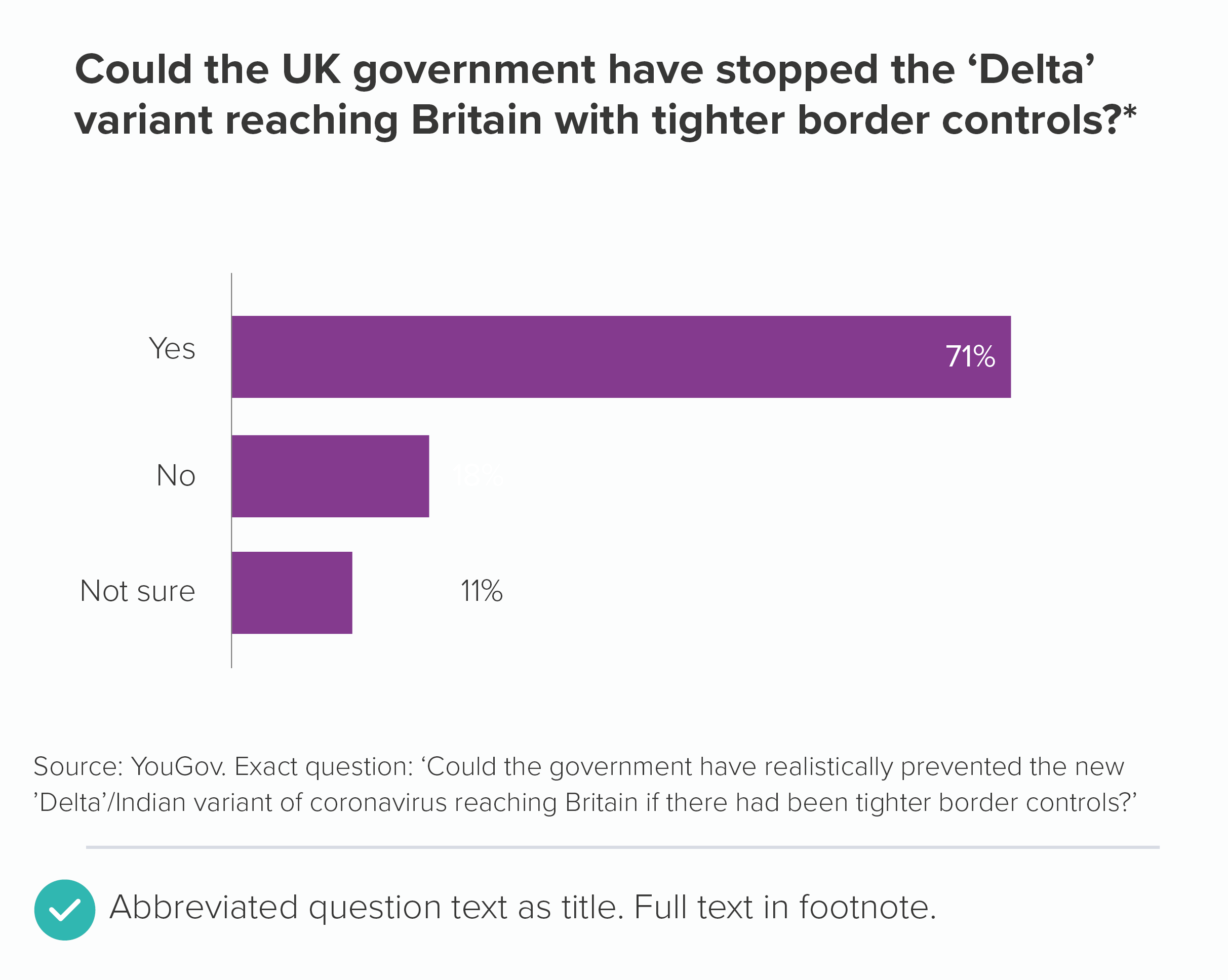

This is based on a 2021 graphic by Yougov (the first design was the one they published). In a vertical bar, the text here would be beaten to a pulp, but even in a horizontal bar, you can see they’ve ended up in trouble.

In this case, it might have been important for YouGov to keep the full text of the statement, so there was no ambiguity about what 71% of people had concurred with. So wrapping was the only option. However, when the labels get this long, it’s always worth trying to bump text up into the title or down into footnotes.

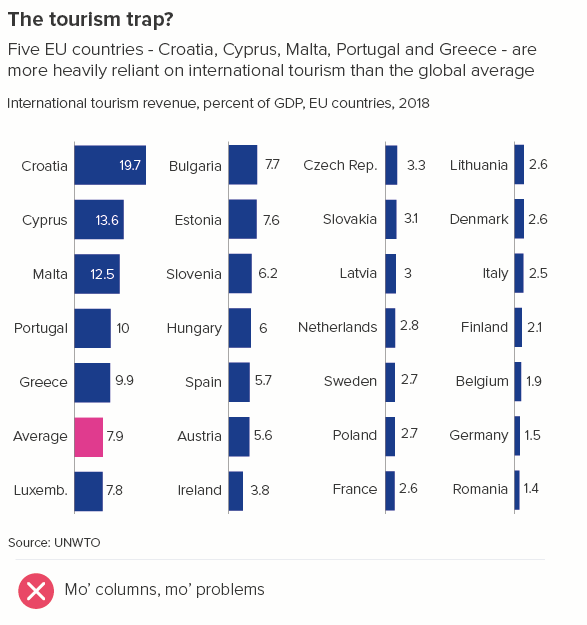

Now for the difficulty spike. Because when horizontal space is limited, horizontal bar labels usually survive intact - you can wrap your way out of trouble. But when vertical space is limited, horizontal bar labels suffer horribly. Just as portrait format (especially mobile portrait) deforms vertical bars, so a rigid 16:9 landscape format plays havoc with horizontal bars.

This is particularly because you rarely have the full height of your 16:9 canvas. A computer screen usually has tabs, address bars, titles, menus, toolbars, search boxes, notifications and other UI detritus up at the top and sometimes status messages, software shortcuts, time and date information and other clutter down at the bottom. With a Powerpoint slide, you lose space to the title and subtitle and possibly chart title at the top. Down the bottom, there are usually statistical caveats, logos, slide numbers and other unnecessary slidejunk. This tends to leave you with a slim letterbox of white space for your chart in the middle.

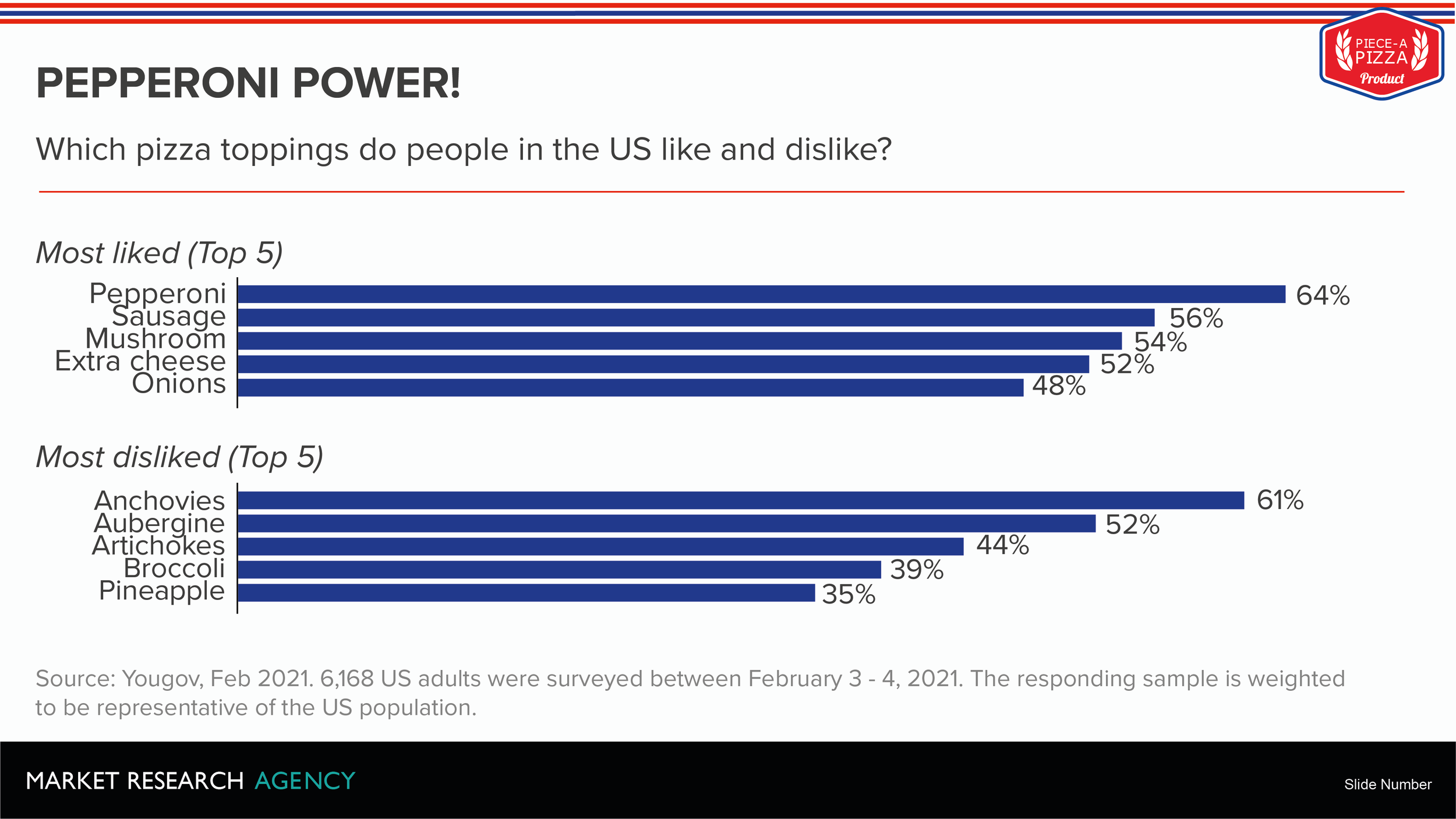

When your canvas is restricted in this way, your horizontal bar labels can start to look mashed together. More than about a dozen, and you have to start reducing font size, or you risk having them overlap. Here’s an example of a squished slide.

The text is getting far too snug here.

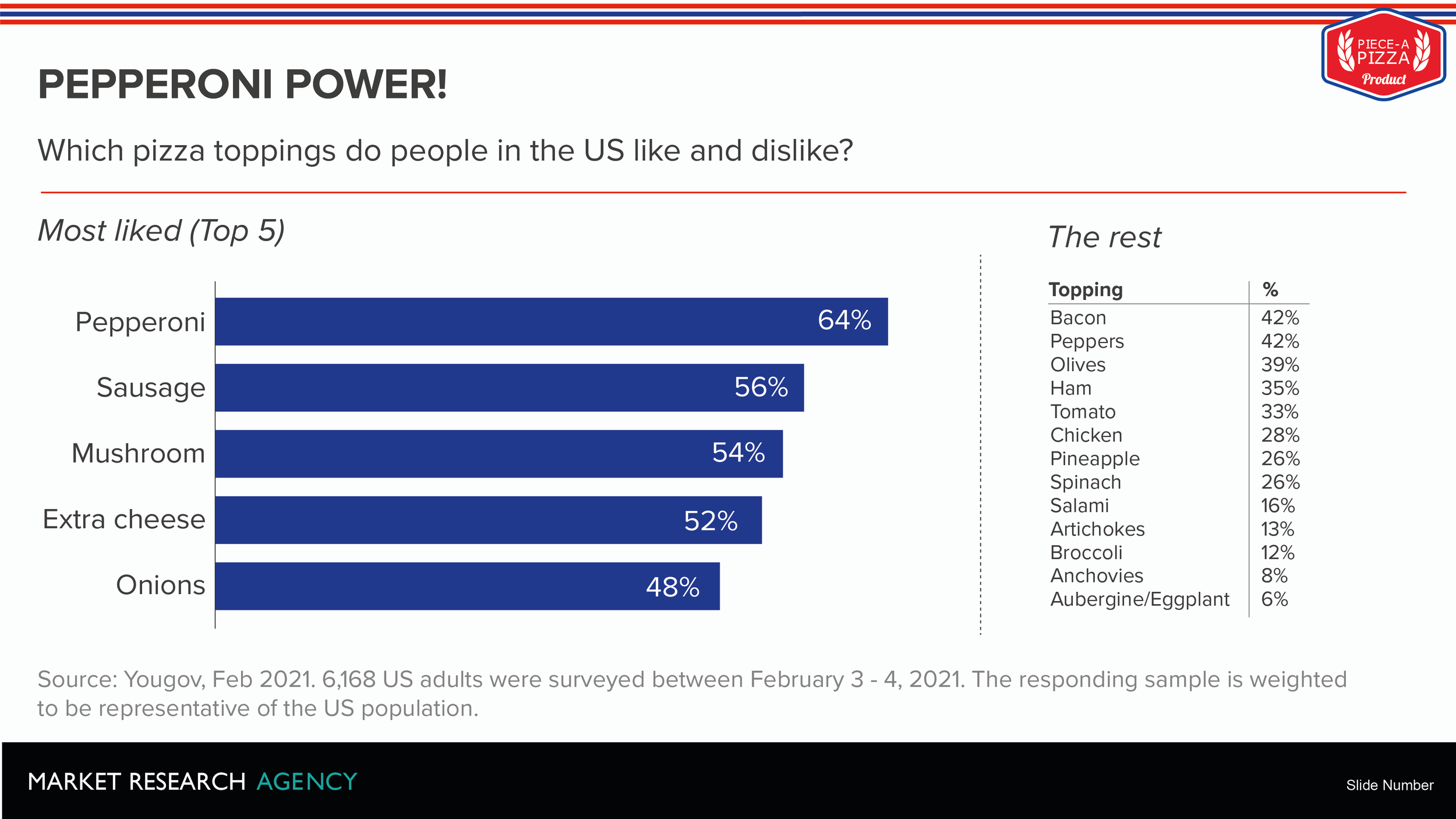

In Powerpoint slides or any other 16:9 canvas, horizontal bars are often best used in combination with other charts. Or placed in columns. That way, you effectively gerrymander more vertical space for each block of bars, and they look less distended. Here are a couple of possible fixes for the chart above.

Be careful though, too many columns of horizontal bars and it becomes harder to compare the shapes (defeating the point of the chart) and your labels become more dominant, making it more text than chart (as we saw in rule 17).

In these cases, it’s best to stop and think about whether your audience really needs all this information at once, and if they do, whether PowerPoint (or indeed a chart) is the right tool for the job.

I am bar chart, destroyer of words

I hope I’ve done enough to persuade you that bar charts do not deserve their reputation as top chart. Yes, they are an invaluable analytical tool. But when it comes to showing others what you have discovered, they are one of many viable options and if text is a critical part of your story (which it should be), they can be the wrong choice. Too often, they are like a leaf blower, blasting text out of the way, leaving it dead and shrivelled up in dark corners.

If you decide a bar chart is going to work best for your story, then remember that the rule ‘Always label your bars and axes’ is unlikely to be helpful. Instead:

Arrange as much text as you can horizontally (push information into titles, subtitles, chart titles).

Limit the number of bars in your chart, so when you use axis or data labels, everything fits.

Consider your canvas size and your dominant narrative metaphor - comparison, ranking, distribution, change over time, something else? - and make sure you haven’t sacrificed narrative integrity for the sake of readability, or vice versa.

Bar charts are one of the hardest charts to get right. Don’t be taken in by their popularity and apparent simplicity. The positioning of text in a bar chart usually takes time and often involves reworking the chart multiple times. When it all clicks, wonderful. But if it doesn’t, it’s not you, it’s the chart, and it is perfectly reasonable to decide that a chart type that treats text as an equal partner might give your story a happier ending.

VERDICT: Follow this rule sometimes

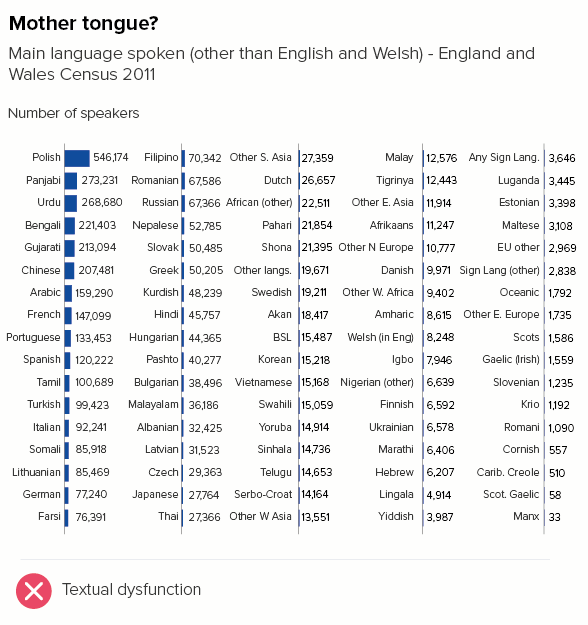

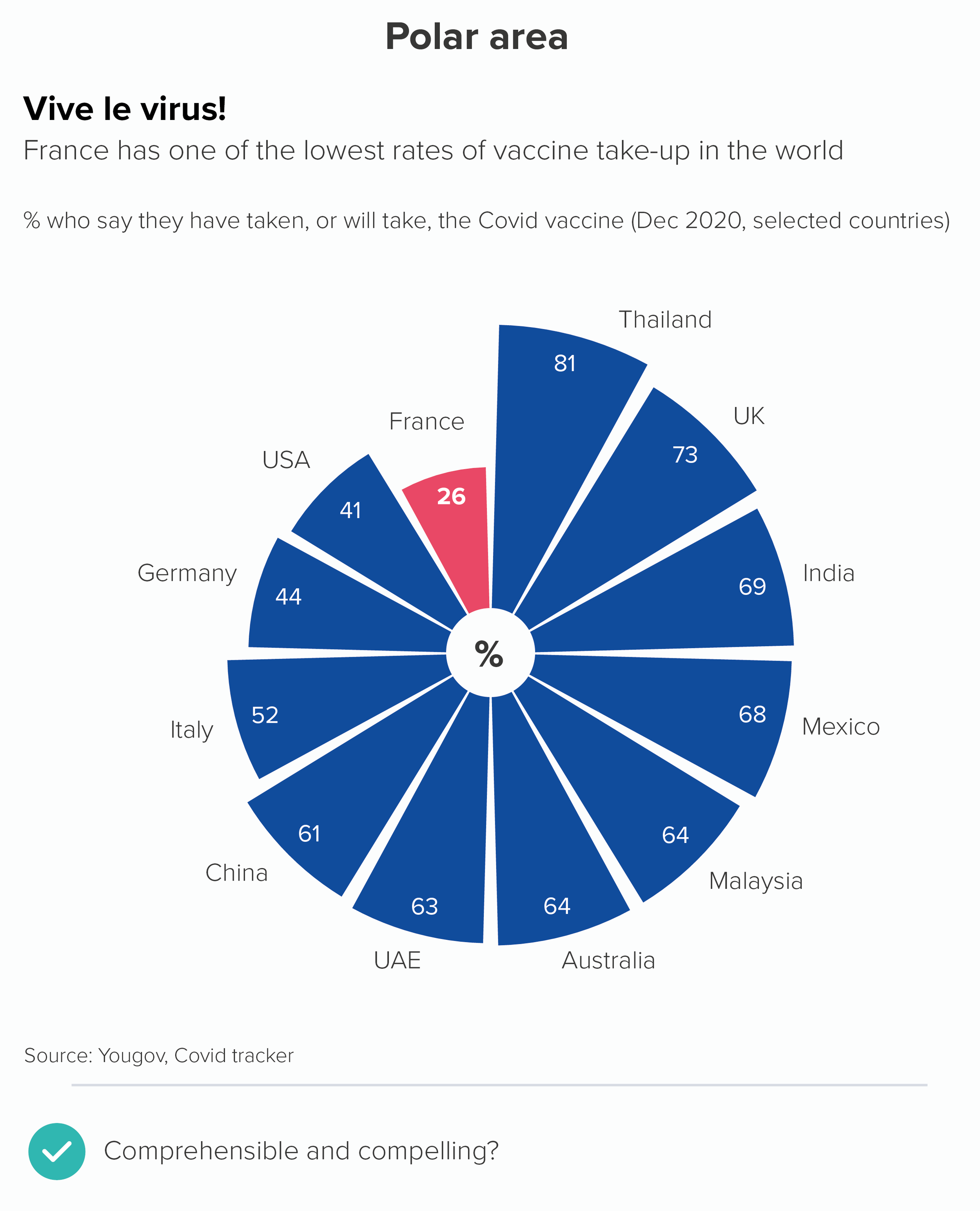

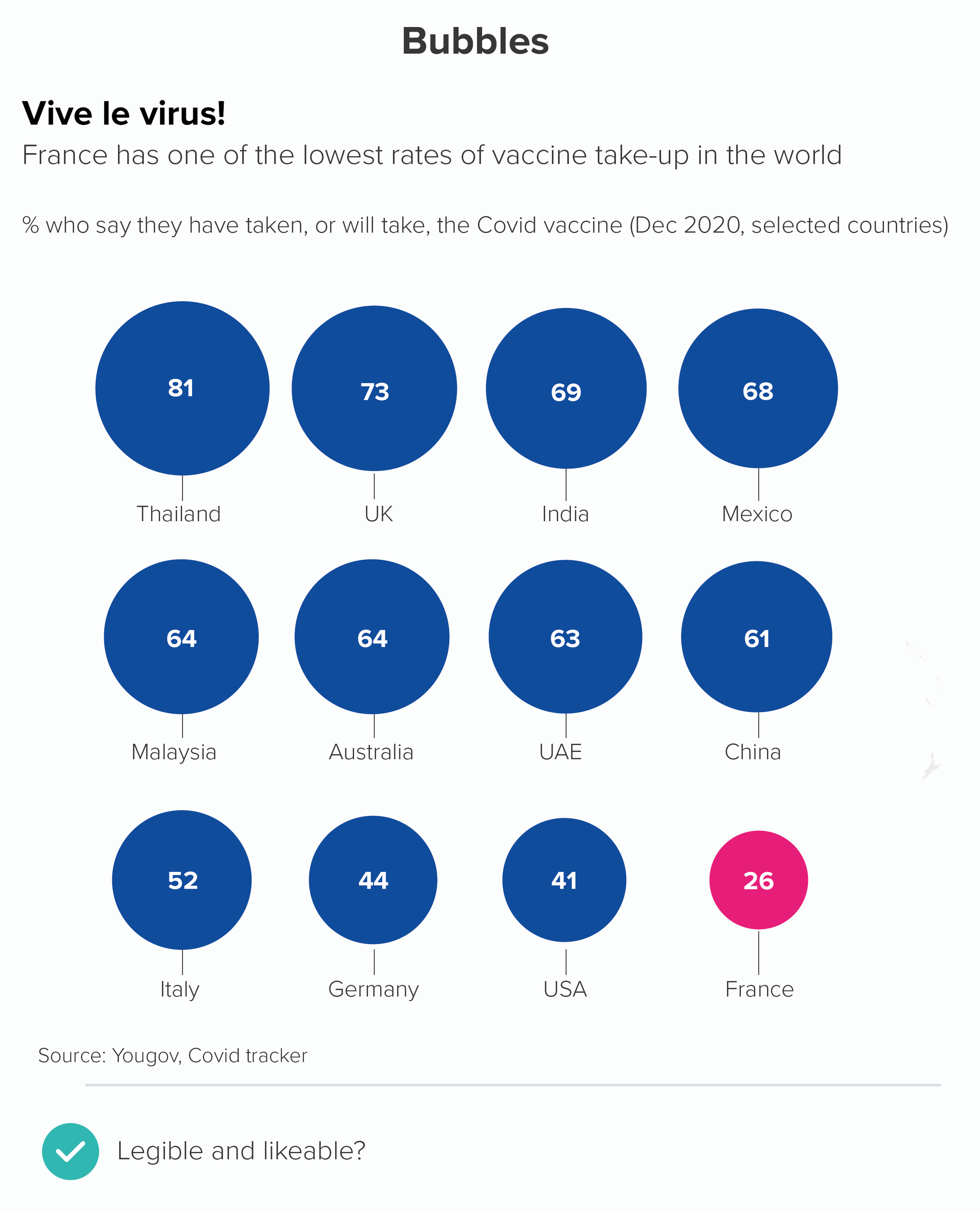

Data sources: Data sources: GDP data - IMF, Plastic pollution - Break Free from Plastic 2021 report, Favourite day of the week in the US - Yougov US, Indian life expectancy - Gapminder, London living and working - London Datastore, Home ownership - Resolution Foundation Game of Homes report, Languages spoken in England and Wales - UK Census via ONS, Boys names in England and Wales, ONS, Youth population - UN Population Division via World Bank, Pizza toppings - Yougov, Vaccine hesitancy - Yougov Covid tracker.

More data viz advice and best practice examples in our book- Communicating with Data Visualisation: A Practical Guide