In this blog series, we look at 99 common data viz rules and why it’s usually OK to break them.

by Adam Frost

Too many bars is always bad; that’s what too many means. But can we put a number on it?

While working with the charting library Highcharts a few years ago, I discovered that their developers had set the maximum number of bars in a vertical bar chart to 1,000. If you try to use 1,001 bars, the chart breaks.

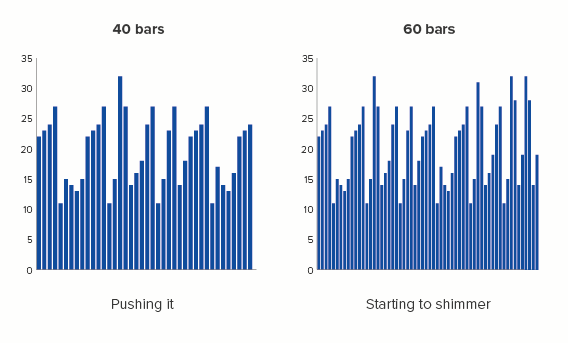

Very wise. But, of course, the chart will have broken long before that. Or at least it will have morphed from a bar chart into an area chart at roughly the 100-bar mark (depending on the chart width), which is a different chart with a different purpose.

This is the main reason why data viz style guides often set a specific limit on the number of bars that you should use. The chief purpose of this chart type is to compare one bar to the rest (your country or company, the largest bar, the average bar) or to assess the distribution of all the bars (e.g. do more people visit our website in the morning or the evening?).

If you can’t distinguish between the bars, or identify which bar or group of bars is different, or read any of the labels because the bars are squashed together, then you’ve ended up turning your original data table into something even harder to read.

So exactly how many bars is too many? In the corporate style guides we have used, recommendations vary. The average limit for comparison stories is usually set at 12 bars. For change over time or distribution stories, it’s usually 24 bars, just because of the frequent need to show change over a 24-hour day.

Compare and contrast

Let’s start with comparison stories: where you want your audience to be able to accurately judge the relative sizes of your bars.

Is 12 bars a sensible limit? Most of the time, yes. If you can bring it down to less than this - seven or eight bars - even better.

Seven or eight bars gives us a hero bar and a manageable number of contextual bars. The more bars you add, the more the audience’s ability to concentrate and care diminishes.

Imagine your bars as characters. In Star Wars, we have perhaps eight key characters we care about: Luke, Leia, Han, Darth Vader, Obi-Wan, Chewbacca and the two droids. Or if you prefer something more highbrow, in Hamlet, we have Hamlet, Ophelia, Claudius, Gertrude, Laertes, Polonius, Horatio and the Ghost.

There seems to be a limit to human bandwidth, our ability to simultaneously consider several objects or concepts. Cognitive load theory suggests that we can only take in between four and seven new pieces of information at once. Psychologists believe that we can maintain an average of five close friendships and an additional ten ‘second tier’ friendships. Our brain defines the limits of our world narrowly, so we are better able to order and navigate it.

In the same way, the world defined by your bar chart will usually be more easily processed if you deliberately limit its size.

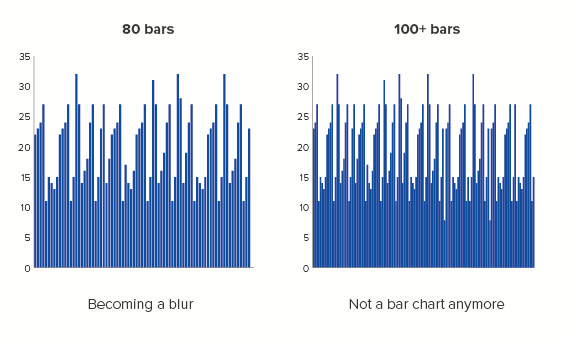

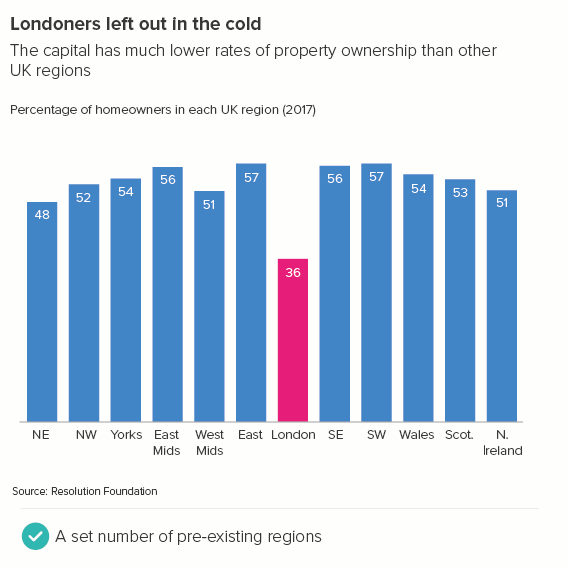

In many cases, this will have been done for you, because these cognitive limits also define and structure reality. There are seven days in a week, twelve months in a year. Most countries are organised into a limited number of regions (e.g. the UK has 12, France has 13). In most sectors, there are a small number of dominant brands - e.g. the UK has eight major supermarkets; the illusion of choice can only be stretched so far. For most large datasets, there is usually a cut-down version which gets all of the attention: the Top 10 for the music charts, the ‘Big Six’ Premier League clubs, the current roster of ‘A list’ celebrities.

If the dominant culture hasn’t kindly whittled down your huge dataset to a shorter list, then you will have to do this yourself, but it’s usually a fairly easy task. If you’ve been crafting a story for an audience - isolating only the most relevant and dramatic information - then you will already have deleted extraneous categories, or set up an ‘other’ category, or grouped similar categories into bands, or perhaps established an average as a benchmark. One of the remaining categories will be the obvious focus (the one the audience is most invested in) and there will be a natural competitive set.

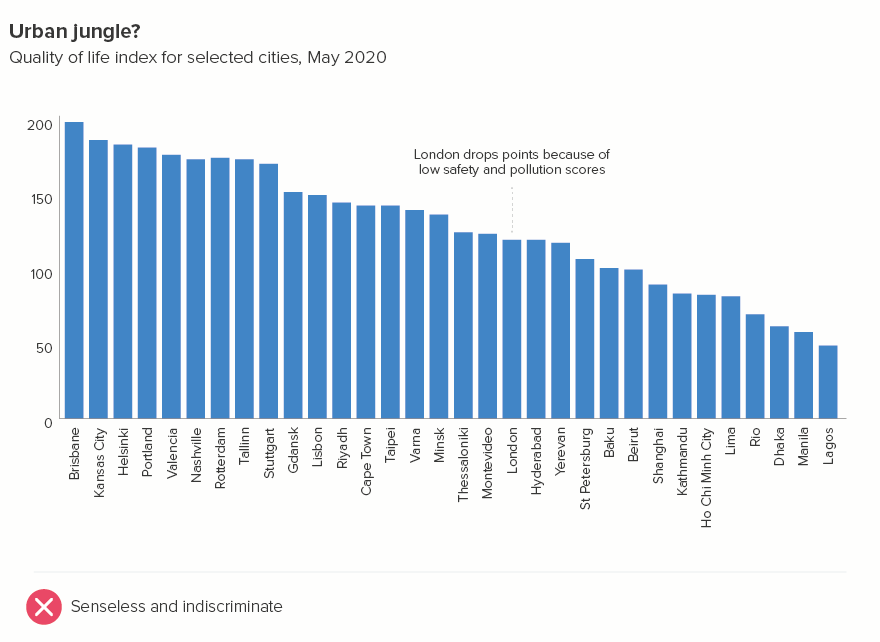

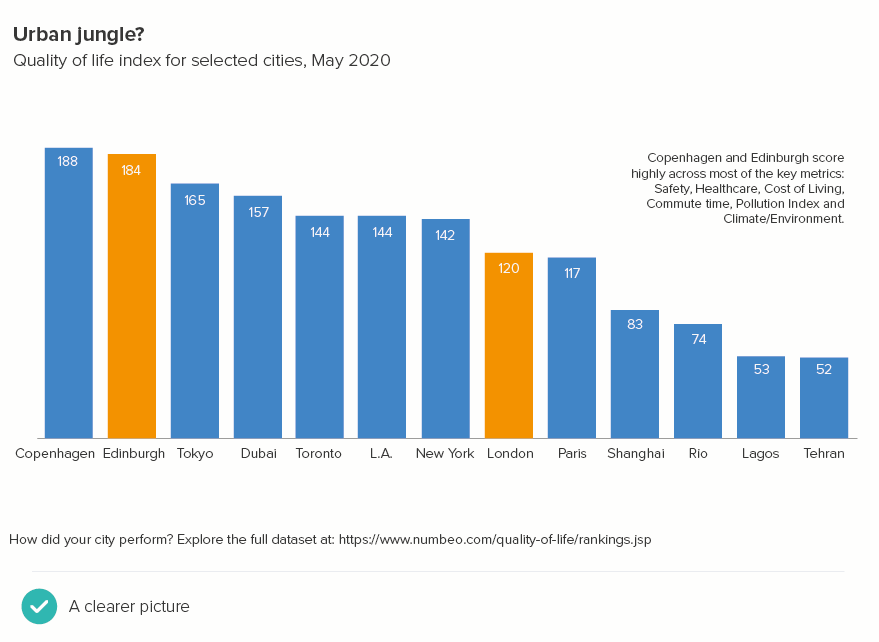

For example, take a look at the two charts below. The subject is the quality of life in different cities. I’m going to assume my audience is based in the UK. In the first chart, I have too many datapoints and I’ve chosen the cities (except London) more or less randomly. In the second chart, I’ve tried to see the world through my audience’s eyes and allowed this to determine the cities I include.

More specifically, in the second chart:

Comparison: I have thought about the cities that London is most often compared with: Paris, New York, Tokyo.

Contrast: I have included a few cities from rising economic powers - Lagos (Nigeria), Rio (Brazil) and Shanghai (China). I’ve also added Dubai - to represent ‘new’ affluence.

Who’s top?: I have included cities in countries that are commonly seen as the most successful - Copenhagen (Denmark) and Toronto (Canada)

Who’s bottom?: I have included the city at the bottom of the list - Tehran in Iran. So my audience is aware of what bad looks like as well as what’s good

What’s the average?: A global city average was not provided in this dataset. It’s probably not helpful in any case - an ‘average’ city is hard to picture.

Amplify the most relevant: Having deleted dozens of cities, and focused on the most pertinent, I now have space to amplify the presence of the UK in this chart. My first chart just had London; in the second, I can also add the Scottish capital, Edinburgh. I have called these two cities out visually. This also gives us an interesting secondary story: competition within the UK, and how Edinburgh is the clear winner. I have also included a second US city (Los Angeles) because, after UK cities, it is US cities that will be most familiar to my audience.

Most critically, my 32 bars have become 13: enough to give my audience meaningful context, but not an overwhelming blizzard of bars. And the labels (just about) fit too - without having to rotate them.

At the bottom, there is a link to the full dataset for those that want the bigger picture. Now the chart is clearer, some of our audience might actually click on it.

So is that our rule? Around a dozen bars, but ideally 7 or 8? Well, sort of. The truth is, although this approach suits many stories, it’s a mistake to put a set number or even a range of numbers (‘between five and 15’) on the number of bars you should use in a bar chart. Because the final number is always narratively-derived. Yes, sometimes there are six infinity stones, Seven Samurai or Twelve Disciples. But there can also be Forty Thieves, 101 Dalmatians or 300 Spartans.

Avengers Infinity War - one of the highest-grossing movies of all time - has 22 major characters in it - according to the faces on the poster* - or possibly 19 if you just count the actors’ names in block capitals. Either way, a lot.

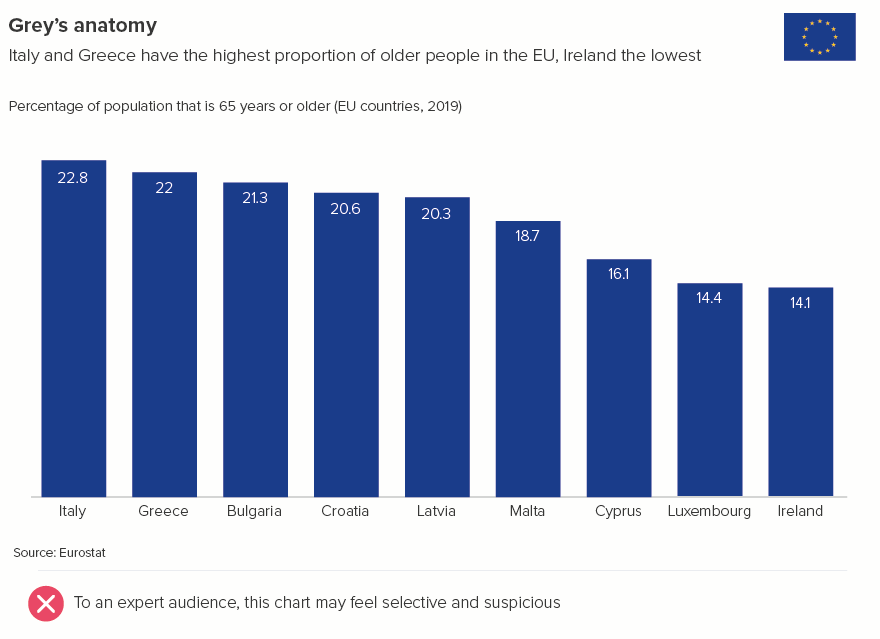

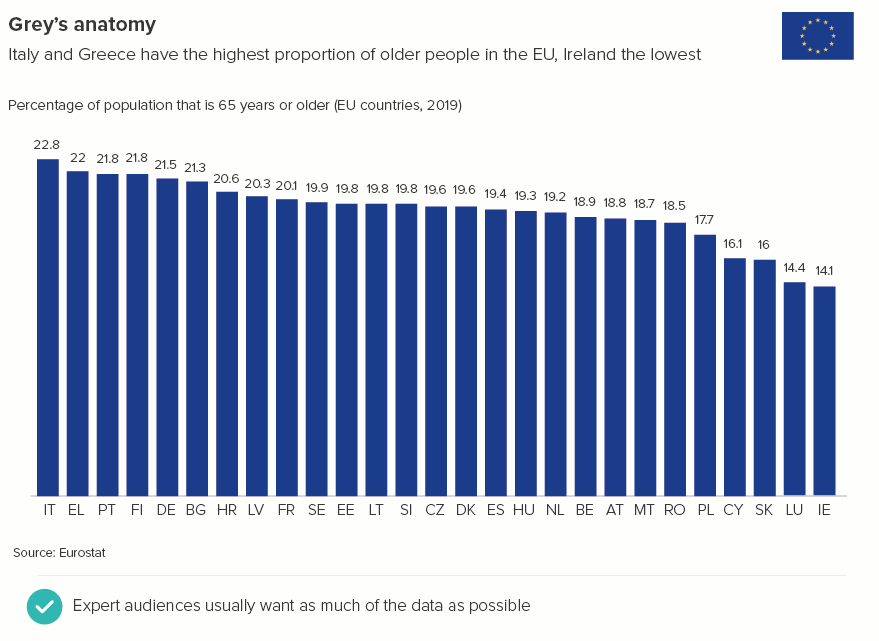

Yes, this is because the audience already knows the characters, so you don’t need to clear as much narrative space around them. But this can be true of your bar charts too - you’re talking to people who are familiar with the dataset already. Say you work for the European Union: your audience will be well aware of the 27 countries that belong to the organisation. Indeed, they will expect any bar chart to feature every country. They will also understand the 2-letter country codes that you will need to use to make all the labels fit. 27 is only too many bars if all the information is new.

Or sometimes you are talking to the general public, but you may have 27 or 227 bars that are all equally important for the story. Perhaps you need to show every state in the USA (50) or every country in the world (195).

When you have these kinds of stories, there are a few techniques you can use to keep your bar charts clear and memorable.

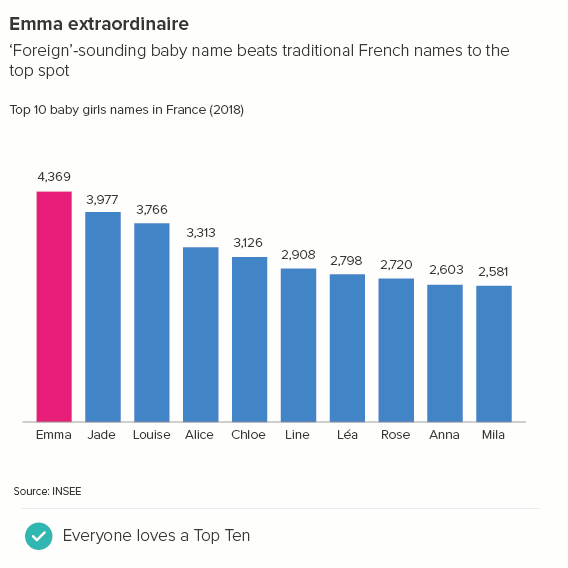

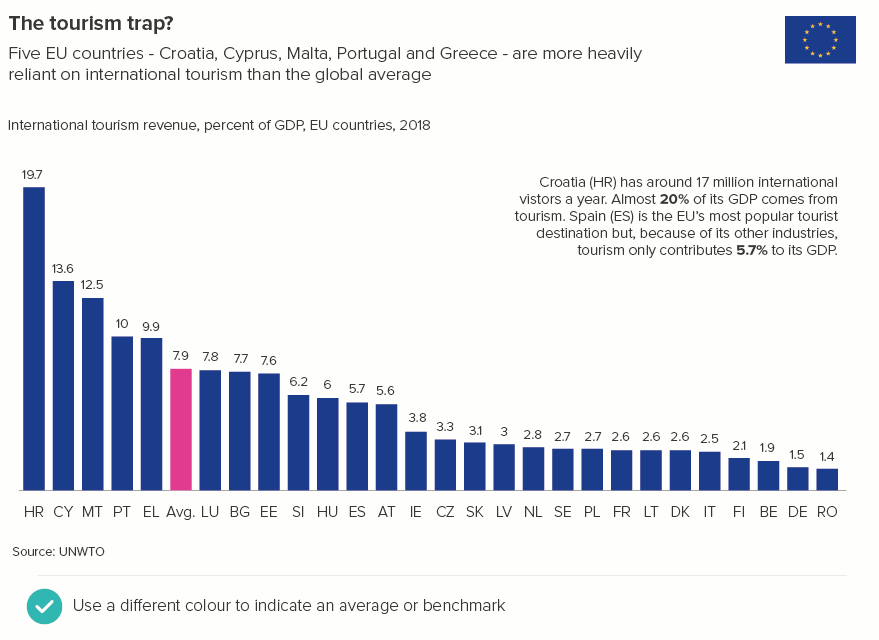

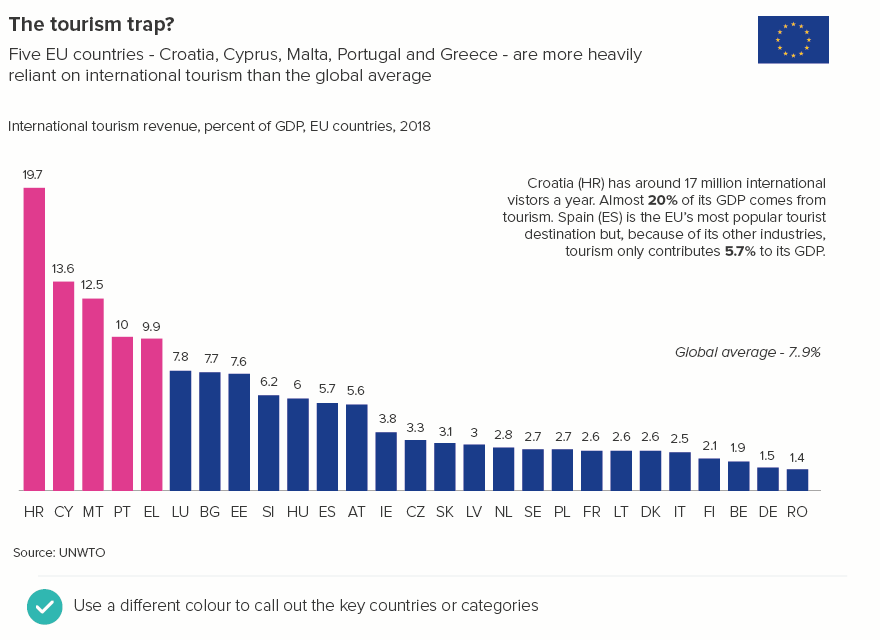

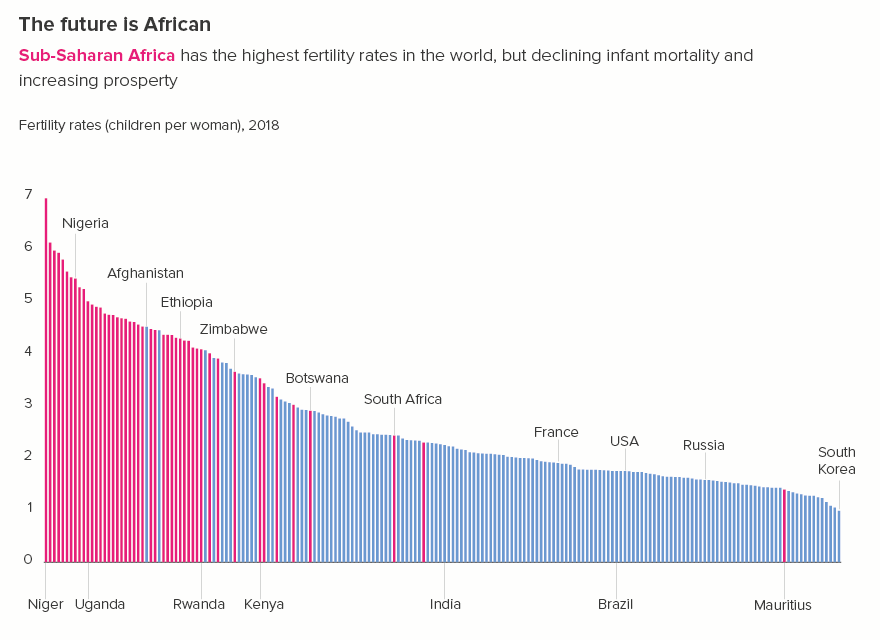

i) use colour carefully

First, keep all the bars the same colour - unless there is a single bar or group of bars that you want to call out. This could be the highest performer, the audience’s own country, or an average.

We’ll talk more about colour in bar charts in a later rule.

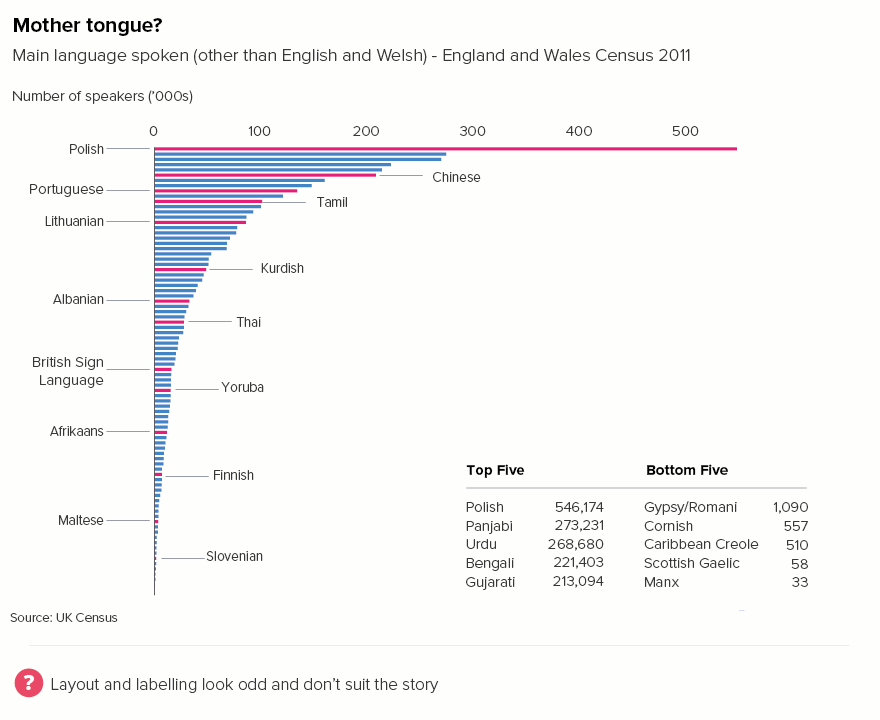

ii) Label strategically

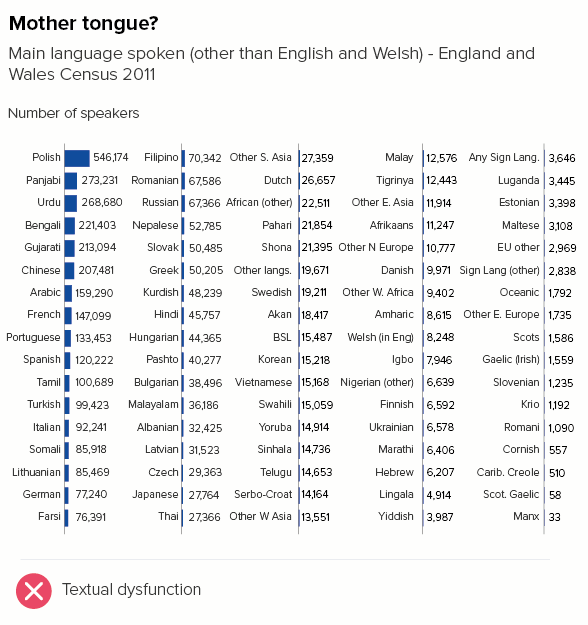

Secondly, you don’t need to label all the bars. With large datasets, labelling everything is labelling nothing because all the text becomes unreadable (tiny font, rotated, overlapping). Just label the bars that are most meaningful to the audience, using the criteria listed above: which bars are useful for comparison and contrast, which are the largest and the smallest, which sit in the middle or act as an average? These labels don’t always need to sit under the axis, you can use connecting lines and have the text sit above the bars too. Also, it’s a good idea to lose most or even all of the numbers. (More about text in bar charts in rule 24).

iii) Combine charts and tables

Thirdly, think about using summary maps or tables alongside your bar chart to provide information that the chart can’t.

If your chart is interactive, you may not need accompanying tables or maps, because your users will be able to roll over or click on the bars to get further information. But I’d still recommend following the other suggestions - one colour for all or most of the bars, minimal labelling - because the chart needs to be readable and interesting before anyone clicks.

Horizontal comparisons

The advice above mainly applies to vertical bars. Horizontal bars require a slightly different approach. You tend to use horizontal bars when:

your canvas is mobile portrait or A4 portrait (they often struggle in landscape format unless used in combination with other charts)

you want to tell a ranking story (with the bars ordered largest to smallest)

you want the labels to be readable

These reasons mean that:

there is usually space for more bars on your canvas

audiences expect more bars because for a story of ranking to be meaningful, you need a Top 10 or a Top 20 or even the whole dataset

all the category labels need to be visible, because that’s why you’re using this chart type - so the labels are legible

In terms of advice then:

If a good rule of thumb for the ideal number of bars is between seven and 12 for vertical bars (depending on the story), for horizontal bars, it’s more like between 10 and 25.

If you have lots of bars, yes, you can drop category labels for vertical bars, but avoid doing this with horizontal bars. This chart’s key strength is its ability to incorporate text, so leaving text out is self-defeating. Furthermore, the fact that horizontal bars excel at ranking stories means that missing out labels can make the story feel misleading or hollowed-out.

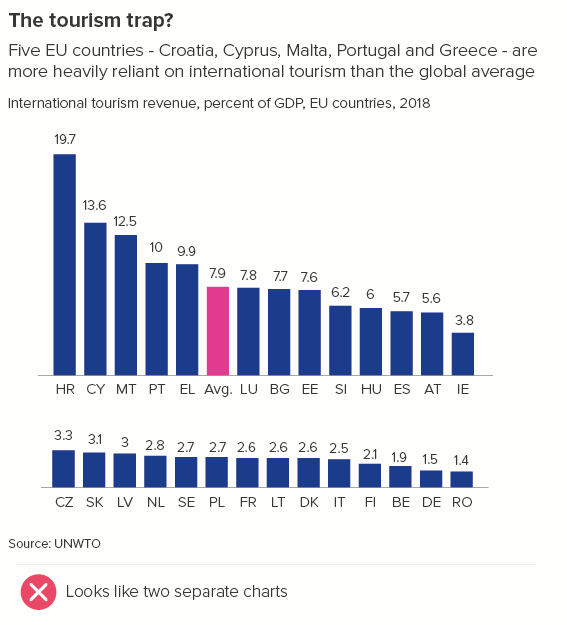

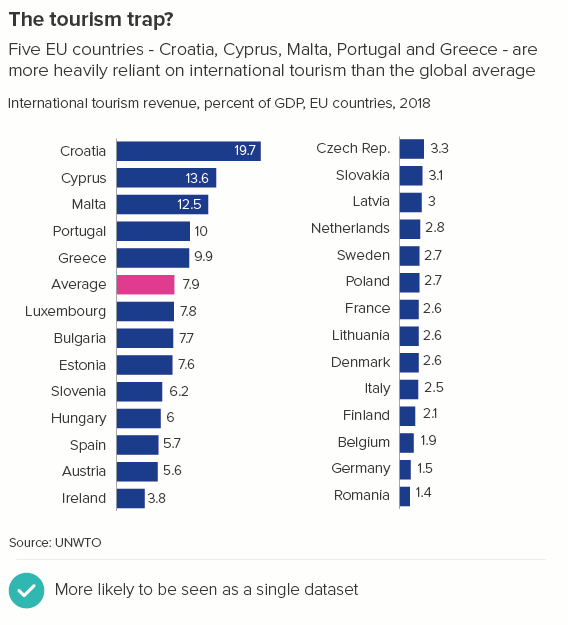

One other piece of advice: if you have a large number of horizontal bars, you can organise them in columns. This is not an option with vertical bars. If you wrap a vertical bar, it looks like you’ve created several separate charts.

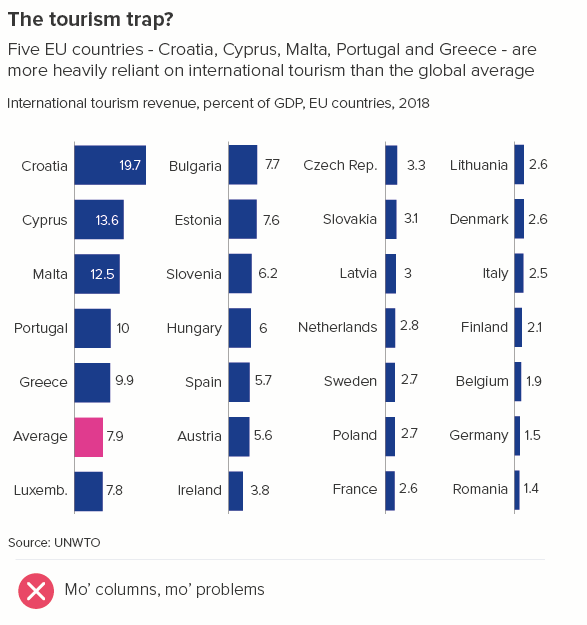

What I would say is that a columnar layout is still a sub-optimal use of horizontal bars, particularly if you group them into three, four or more columns. Two columns is probably the maximum. Otherwise you lose the ability to compare the bars (how much bigger is Croatia than Romania in the first chart below?) Also there’s a risk that you end with a chart that is mostly text instead of mostly shapes and therefore not a chart at all (the second chart below).

As with any chart choice, it’s also worth thinking about whether an alternative might tell your story better.

Alternative options

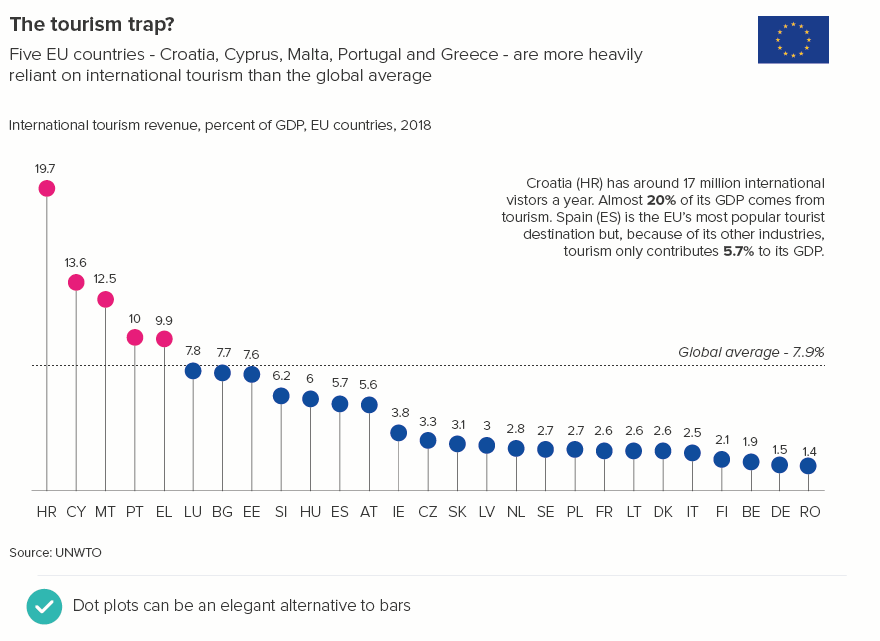

When you need to compare a large number of datapoints, does a field of bars really help your audience access and understand the underlying numbers? The end of each bar, so critical for understanding the chart’s meaning, can become blurred by proximity to its neighbours. Dot charts make it easier for your audience to pinpoint each category’s value. They are also less visually overwhelming as there is no fill to generate visual after effects (e.g. the McCollough effect) or optical illusions.

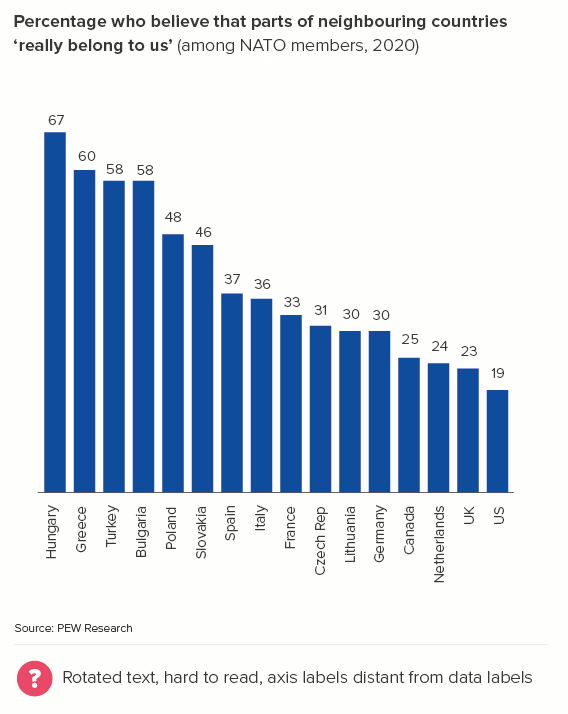

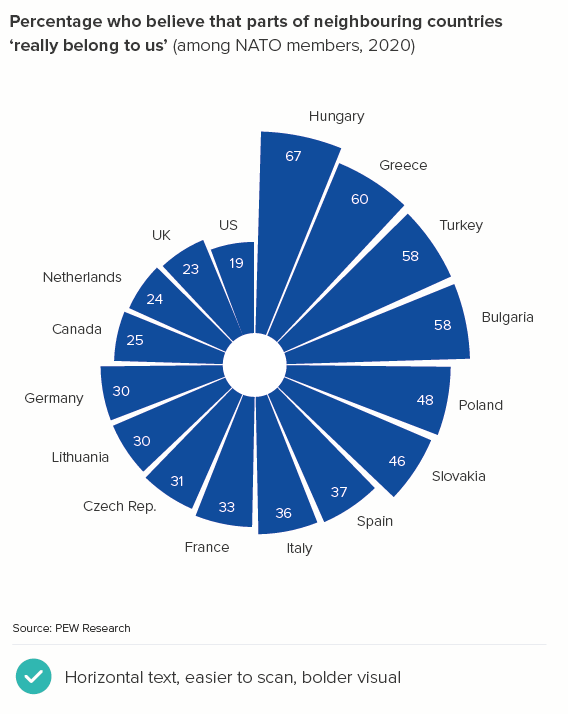

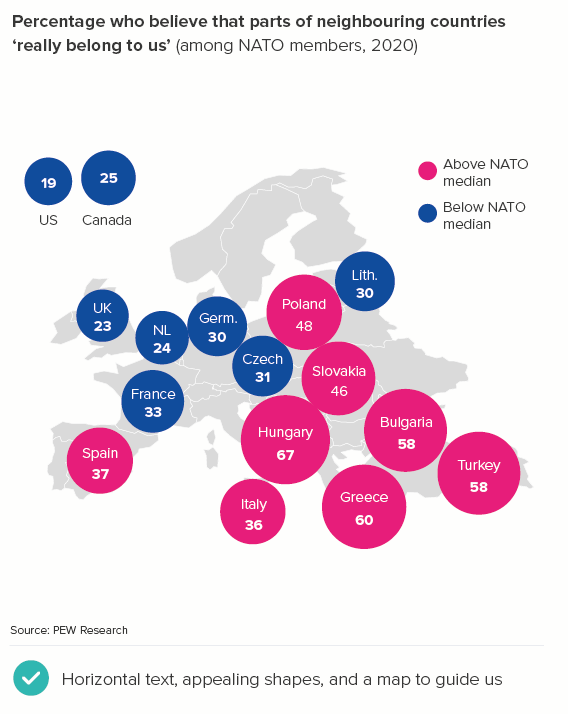

It is also worth considering polar area charts, bubble tables and other proportionately-sized shapes. The precise differences between the datapoints are sometimes harder to judge, but these charts can be more visually appealing and easier to label than vertical bars. Or, if you have geospatial data, there are always maps - which everyone loves and which we will discuss in more detail in later rules. I’ve put some examples below.

Change over time

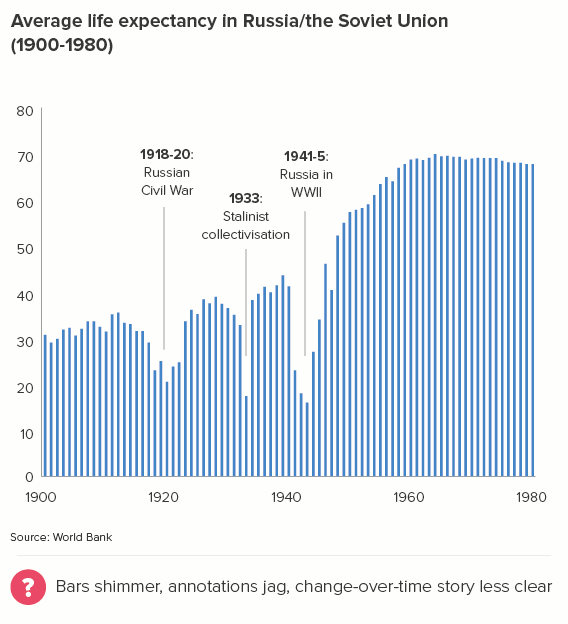

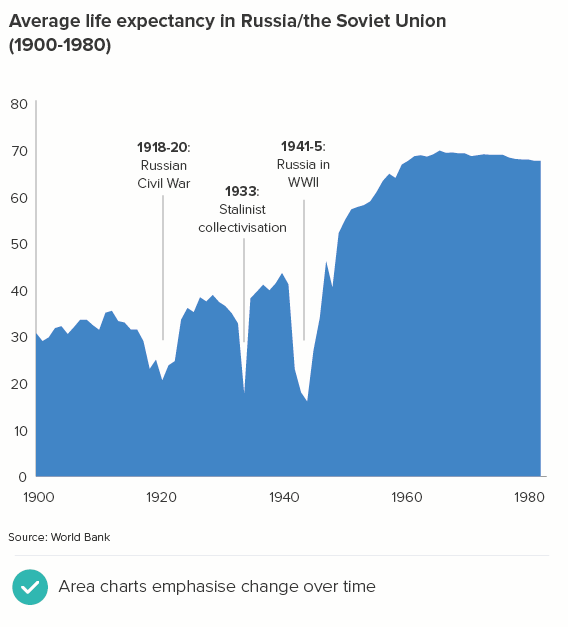

For change over time stories, when you have lots of bars, many people quite rightly switch to a line or area chart.

Line and area charts also help people to understand that the key story is the change in value - the trend, the shape, the direction of the data. (The line across the page becomes the data’s heartbeat).

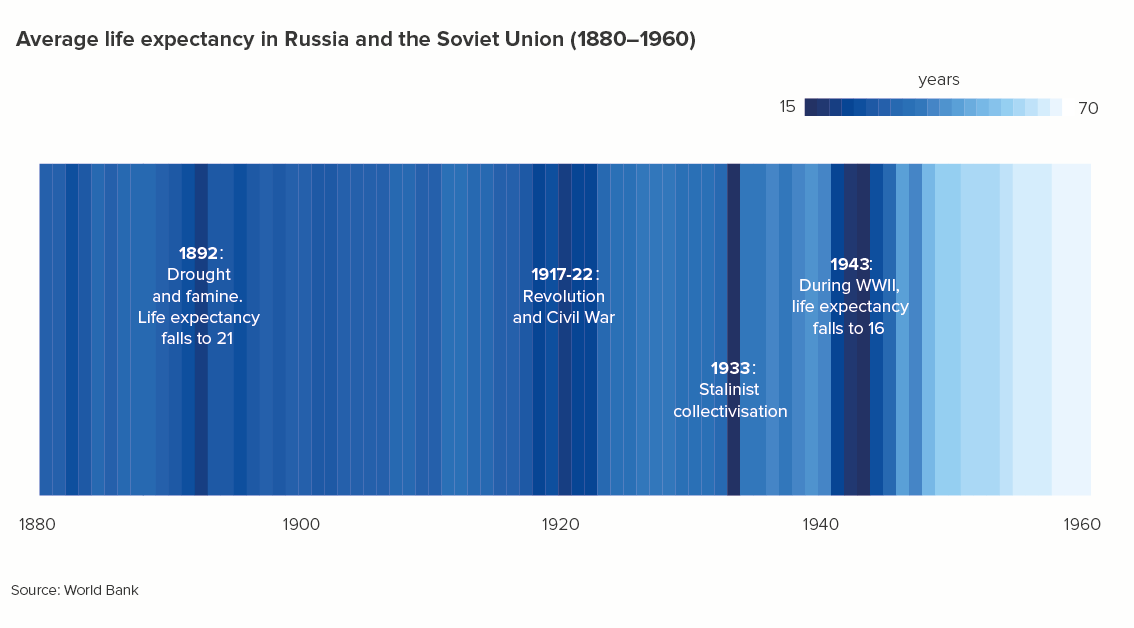

Another innovative alternative to a crowded bar chart is Ed Hawkins’s climate stripes. Hawkins originally used his chart to visualise the change in temperature over the past 200 years, but you can use them for other change-over-time datasets too. Flourish have recently added a climate stripes chart maker to their excellent online tool.

Evenly distributed

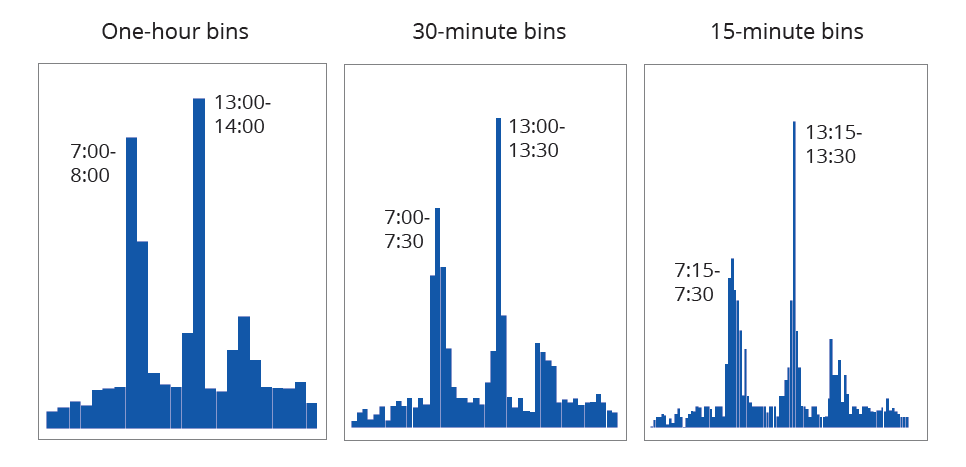

Let’s conclude by briefly considering distribution stories: this is when you’re trying to show your audience the spread of your data, usually by ‘binning’ or ‘bucketing’ the data. This involves dividing all the values in your dataset (e.g. hours in the day) into a series of equally-spaced intervals and plotting them on a type of bar chart called a histogram.

When you are using histograms to analyse your data, the number of bars/bins is often mathematically-derived (most commonly: the number of bins = the square root of the number of values you are binning). However, this tends to give you some odd divisions. For example, say I had 10,000 daily visitors to my website and I wanted to know at what time these visitors first arrived on the site. The square root of 10,000 is 100 - so I would have 100 bars/bins. Each bin would be 14.4 minutes long. My intervals would be 0:00:00-0:14:24, then 00:14:24-00:28:48 and so on. Not a human-readable format.**

This isn’t a huge problem when you are analysing. But when you use bars to communicate distribution stories, you should use bin widths that make sense in the real world. In my website example, you might use divisions of an hour, thirty minutes or fifteen minutes. Note that we are not worrying about a minimum or maximum number of bars. It is a question of how we most clearly show the overall spread of the data and any important patterns or outliers.

In this example, adapted from a dataset for a media website, we would end up using the 15-minute bins, because this gives our audience the most useful information. Yes, most website users visit the site at lunchtime - between 13:00 and 14:00 as the first chart shows. But what’s even more surprising is that, within that one-hour slot, the majority of users visit between 13:15 and 13:30, fifteen minutes after their lunch hour starts, presumably after they’d picked up a sandwich and started to eat it al desko.

So I’m not sure setting a maximum number of bars in a histogram is helpful, as you might never find that critical exception or outlier. Furthermore, you are usually showing distribution stories to more data-literate audiences and they will not only already know the data, but they can usually tolerate higher levels of information density.

When presenting your distribution chart however, it’s still worth considering all of the guidance around crowded vertical bars. You can see this in our example histograms above. Use a single colour, minimise labelling, annotate only the most pertinent bars. And if the story isn’t clear enough, switch to a different chart. Or just pull out the key insight, and dramatise that.

To conclude then, do everything you can to limit the number of bars for your audience. Remember that humans cannot cope with large amounts of new information in a single sitting. However, sometimes what your audience demands is more detail, more data, more depth, and in these instances you should minimise colour, labelling and other visual clutter to make the story in that crowded bar chart stand out. And if that still doesn’t work, then your chart’s days are clearly numbered. Time to raise (and raze) the bar.

VERDICT: Breaking this rule is unavoidable

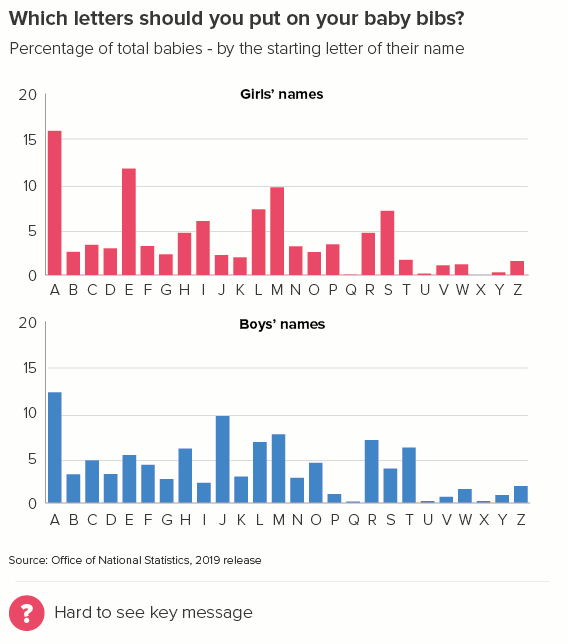

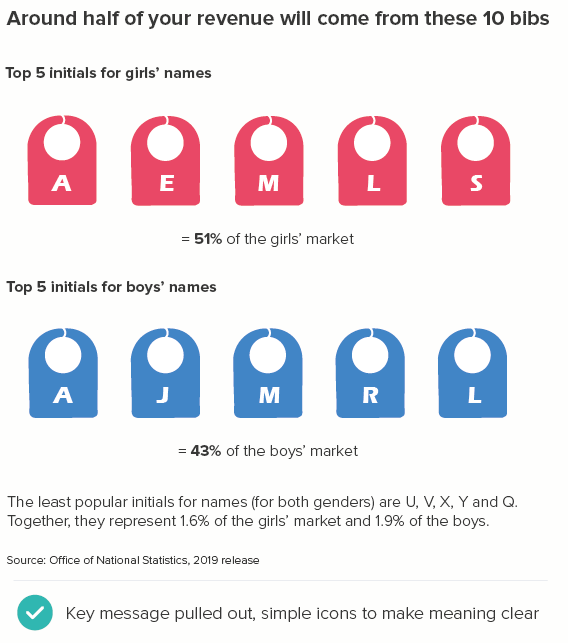

Data sources for charts: UK home ownership levels from Game of Homes - Resolution Foundation, French baby names from INSEE, Quality of Life index from Numbeo (extracted May 2020), Older people in the EU from Eurostat, Fertility rates from World Bank, Tourism data from UNWTO, Most common languages in England and Wales from UK Census 2011 (via ONS), Russia life expectancy from Gapminder/World Bank, Most popular baby initials, derived from ONS 2019 release

*Vision, Scarlet Witch, Dr Strange, Wong, Thanos, Black Panther, Captain America, Iron Man, Thor, War Machine, Star-Lord, Black Widow, Spider-man, Drax, Gamora, Nebula, Rocket, Bucky, Hulk, Mantis, Shuri, Okoye

**Sometimes, you might use bars of varying widths in your histogram. The guidance for a standard bar chart doesn’t apply in these cases, so I won’t cover these charts here. Also, I think they look confusing for non-statisticians and would only ever use them for analysis, never communicating with others.

More data viz advice and best practice examples in our book- Communicating with Data Visualisation: A Practical Guide